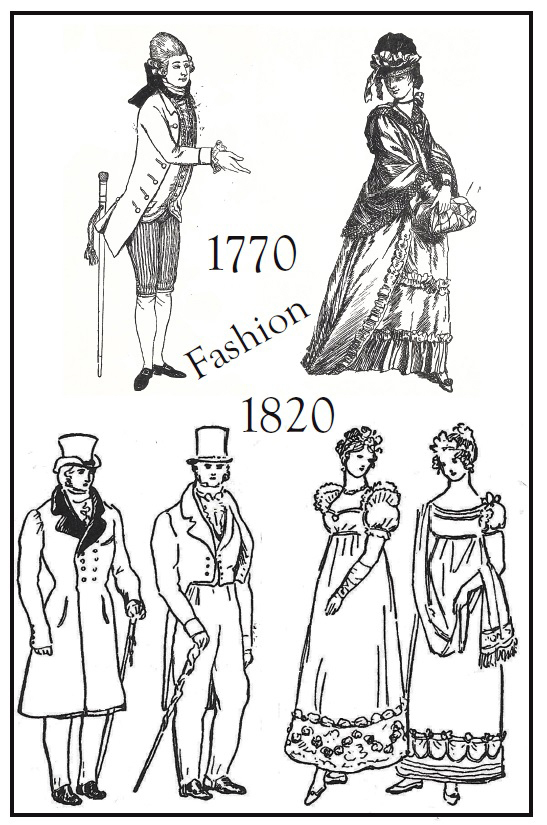

Fashions of 1770 and 1820. The latter fashions might have been worn to statehood parties in Maine.

(On March 15, Maine will officially celebrate its 200th birthday. The state will memorialize the occasion with the official Statehood Day Commemoration, beginning at 1 p.m. at the Augusta Armory. The program will feature the Maine Army National Guard color guard; a land recognition with Maulian Dana, of the Penobscot Nation; a review of Maine’s story with State Historian Earle Shettleworth; reflections from Poet Laureate Stuart Kestenbaum; addresses from our congressional delegation; and performances by the combined Bicentennial Choir and Bangor Symphony Orchestra, debuting the specially commissioned piece by Colin Britt “So Also We Sing: A Maine Trilogy.” In this month’s bicentennial column, Louise Miller, Lincoln County Historical Association’s education secretary, draws upon her extensive knowledge of 18th-century clothing and costumery to describe how citizens might have dressed at statehood parties in 1820.)

Buzz and excitement – someone will certainly hold a party! 1820 – a new century was upon the country. Within the last 50 years a revolution had been fought; no longer English subjects, Americans were born; the effects of the 1807 embargo had damaged Maine’s economy; the War of 1812 had come and gone; then came March 1820.

After another struggle, this time between the people themselves who populated Maine, and between their representatives in Washington, D.C. and the federal government, the declaration – Maine was her own state. Certainly, there were parties.

What to wear to the statehood celebration party must have been on the minds of a number of Maine ladies, and men. Within the last 50 years the yards and yards of cloth that made up a lady’s gown, creating a voluminous skirt supported by large petticoats, had shrunk noticeably, bringing the silhouette to a much more slender outline. Waistlines went from being at the waist, in the 1770s, up.

Favored fabrics such as large, patterned brocades in silk and linen, and large prints in general, were no longer the choice of the day. By 1820 the lightweight wools, linens, and silks suited the new fashion styles well, and competed with the new craze for Indian cottons. These new printed fabrics featured small designs scattered across the cloth, rather than decorating it heavily with color.

For daywear and evening socials, white was the most popular color for ladies’ dresses. Light colors of pink, blue, and yellows were also favorites. For ladies of means, Kashmir shawls would have been a crowning touch to a party outfit. These long, beautiful shawls (some 50 inches wide by 100 inches long) were woven with colorful patterns.

It is to be assumed that gentlemen also wished to dress for the occasion. A gentleman’s dress outfit still required white shirt, vest, coat, and trousers as the basic pieces. The shirt itself had changed little between the 1770s and 1820. The waistcoat, by 1820, actually ended at the waist. Where breeches, men’s pants that ended just below the knee, were still being worn at the beginning of the 19th century, by 1820 they had lengthened to the ankle and trousers came into general wear. The gentleman’s coat, which had boosted tall collars high enough to touch the ear at times during the previous 20 years, by 1820 was fashionable with collars that lay flat against the body of the coat. The 1820 coat itself had two popular variations: one style resembled what one would think of today as “tails”; the other was an A-line overcoat buttoned generally only to the waist.

Even in men’s fashions there were popular colors in 1820. Black, dark blue, brown, and gray were among the most common colors for coats and trousers. Striking fabrics of stripes and patterns were popular for the waistcoat.

Stepping out for a statehood party would definitely create some buzz in one’s household, if not the whole neighborhood.