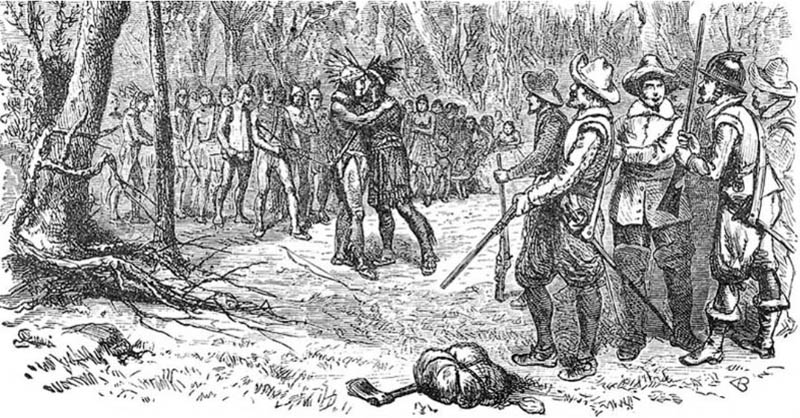

Wawenock reunion at Pemaquid. (Print courtesy of Stephen Luscombe)

On March 16, we will celebrate the 400th anniversary of an event that most Mainers know only vaguely from an elementary school history lesson. The occasion is worth remembering not only because it was an important moment in history, but also because at its root were issues similar to what we are facing today — the pandemic and racial inequity. On that date in 1621, Samoset, a Wawenock sagamore from Pemaquid, walked into Plymouth Plantation and greeted the Pilgrims.

He was lucky they didn’t shoot him on sight. The Pilgrims were exhausted and edgy; half of their company had died of illness over the winter, leaving them terribly weakened and vulnerable. They were so afraid that the Natives would see how few of them were left that they buried their dead in the middle of the night in unmarked graves. All that winter they saw fires and heard sounds of people around them, but no one approached them.

They knew they were not welcome in this land. Their only encounter with Indigenous people had been on Cape Cod when they were scouting for a location to build their settlement. Early one morning their scouting party was attacked by the Nauset, who had good reason to be angry. Six years earlier another Englishman had come to their shores and abducted seven of their kinsmen. They were never seen again.

On March 16, the men of Plymouth gathered to go over military orders. Samoset caused an alarm when he “very boldly came all alone” toward them, carrying a bow and two arrows. It would have been instinctive to defend themselves against an intruder, but he quickly saluted and greeted them in English. Their shock at hearing him speak their language probably saved his life.

Perfectly at ease with the Pilgrims, he told them he came from the east, “a day’s sail with a great wind, and five days by land,” and had learned to speak English from the men who came there to fish. By all measures, he was very far from home. So what led him to Plymouth, and why alone? Samoset’s story, it turns out, is much more involved than we knew.

Years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, English speculators looked at Midcoast Maine as a possible location for a colony. They sent Capt. George Waymouth in 1605 to scout for a suitable place as well as goods that would bring a profit — furs, fish, timber, and precious metals. Waymouth landed in Wawenock territory, at the St. Georges Islands in Muscongus Bay. Samoset’s band from Pemaquid was there visiting, and this was likely his first encounter with the English. It would end in violence and broken trust.

Curious about the strangers, the Wawenock paddled out to Waymouth’s ship and made contact. They were fascinated by English peacock feathers, mirrors, and candy, but frightened by their snarling mastiffs and exploding muskets. Their curiosity won out, however, as well as their desire for biscuits and peas. For several days Waymouth encouraged trade with the Wawenock, but after a tense encounter he was done pretending friendship. Waymouth had his crew kidnap five Native men, all from Pemaquid, and took them to England.

Taking slaves was nothing new for the English, who justified their actions by claiming that Indigenous people were uncivilized because they weren’t Christians. They planned to return to Maine with these men as their guides and interpreters, and arrogantly assumed the captives would comply. While the Wawenock were in England they would have seen things beyond their imagining; buildings made of bricks and stone, bridges, horses, carriages, and books were all unknown to them. So were abject poverty and the excesses of a wealthy class. In their culture everyone shared in the wealth of a good harvest or a successful hunt, and no one took more than he or she needed to survive. They were learning a lot about the Europeans.

Two out of the five kidnapped men returned to Pemaquid, much to the Wawenock’s astonishment. They naturally assumed their kinsmen had been murdered. Samoset must have listened to their stories about England with wonder. In 1607 he got the chance to see an English settlement in person when the Wawenock visited the Popham Colony in Phippsburg that September. He would have been an eyewitness to the fort under construction as well as the first English ship built on American soil, the Virginia.

The English were counting on their Wawenock interpreters to set up a trade network for them, and at first relations with the local people were cordial. But feelings soured after the death of the colony’s president, George Popham. He was succeeded by the young, brash, and racist Raleigh Gilbert, who so bullied and mistreated the Natives that they turned against him. Gilbert’s actions were reckless because the English were not prepared for a harsh winter and depended on the locals for food and vital information about the area. Losing the support of the Indigenous community was one of the main reasons Popham Colony failed. Gilbert and his men returned to England in 1608.

After the Popham Colony was abandoned, the original investors gave up on the idea of a permanent settlement and sent ships to the Pemaquid area seasonally to fish and trade. This is how Samoset got to know English fishermen and learned to speak the language. It was a difficult time for the Wawenock, for they had become embroiled in the Micmac War, an intertribal conflict that involved Native people from Nova Scotia to Saco. Samoset, now an adult, would have joined his brothers in the fight. The war lasted more than a decade and left his people devastated. They were in no condition to fight off the next enemy, this time a microscopic one, during the epidemic of 1616-1619.

With so many Europeans coming to Maine, it was inevitable that some of their pathogens would be passed to the Wawenock. Indigenous bodies had no immunity to European diseases, and this one — which has never been identified — killed up to 75% of the Native populations where it spread. This meant that of approximately 100 Pemaquid Wawenock, probably only 20 survived. Samoset would have buried the rest.

It was at this time that he became a sagamore, or leader of his people, and the burden fell on him to protect his band and help them recover from exhaustion and trauma. They were far from safe. Even though the Micmac War had ended, the Micmac continued to send raiding parties to the coast of Maine and he didn’t have the manpower to resist them. This may explain why he left soon after the epidemic subsided for Wampanoag territory in Massachusetts — he may have been looking for survivors to help him repopulate his band in Pemaquid.

Thus we find Samoset walking into Plymouth Plantation in March 1621, alone and far from home. Given his life experience, he was the perfect man for the job. He knew the English well, could speak their language, and was a seasoned warrior accustomed to conflict and danger. He had already survived more than most humans — hostile foreigners coming to his homeland, a decade of war, and an epidemic that killed most of his family and friends — and he faced down this new threat with remarkable self-assurance. It’s possible he was not intimidated by the pale, sickly Pilgrims. Or perhaps he had suffered so much that nothing frightened him anymore. Either way, he walked into Plymouth Plantation with complete confidence that he would make this meeting a success.

And he did. With his open and friendly manner, Samoset quickly put the Pilgrims at ease. He answered their questions freely, told them about the Wampanoag who lived in the area and the sickness that had killed so many of them, asked for beer, and ate the Pilgrims’ food with appreciation. All the while he was taking their measure so he could report back to the Wampanoag. Samoset returned a few days later with Massasoit, their grand sachem, and helped negotiate an agreement between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims that laid the foundation for peace between them for over 40 years.

Soon after, Samoset left for Maine, where his trials and contributions were far from over. Through all the hardships to come he managed to keep the peace with the English, recognizing like Massasoit that this was in the best interest of his people. He would make accommodations but not be bullied. Ultimately, though, it was the Englishman’s sense of superiority and greed for Indigenous land and resources that won out, resulting in decades of war and the marginalization and displacement of the Wawenock and other Native people.

Four hundred years later as we struggle with the pandemic and racial inequality in this country, Samoset’s story feels uncomfortably relevant. An honest examination of our past is necessary in order to reconcile with it and forge a better path forward. The 400th anniversary of Samoset’s walk into Plymouth Plantation is an excellent time to recognize what he and his people endured and achieved, as well as honor his diplomatic handling of that important first meeting between Indigenous people and the Pilgrims.

(Jody Bachelder grew up on the Pemaquid peninsula and is currently writing a biography of Samoset and an early history of the Wawenock. Publication by DownEast Books is expected in the spring of 2022.)