Bronze street sculpture in Budapest: “The Paul Street Boys,” based on the young adult novel of the same name by Hungarian author Ferenc Molnar. (Photo courtesy Paul Kando)

The inimitable Mr. Kando: Late last month, I wrote in this column about the importance of the arts – or rather, a number of people helped me write about the importance of the arts, sending me thought-provoking responses to the question, “Why are the arts important?”

One of those people was Paul Kando, whom readers will know as the writer of the informative sustainability-focused column “Energy Matters,” which appears weekly in this paper. One of the sage things that Kando said: “An artist – be it a professional or an amateur or even someone who simply enjoys the artworks of others – is a person apt to see multiple paths to solving even the most mundane or most difficult technical problems. It is no accident that many of the world’s greatest scientists were also artists.”

Writing to me later, Kando said that my question had made him think of his own arts education in high school when he lived in his native Hungary. (Kando moved to the United States at age 20 after the 1956 uprising against Soviet occupation.) He told me that “the arts were considered fundamental to being civilized” and offered to write at greater length about his formative arts experiences for my column if I wished.

Of course, I took Kando up on his offer and I now turn “Artsbeat” over to him:

My art education

By Paul Kando

Wrestling with the theory of relativity in high school, the science seemed discouragingly challenging. Mrs. Kanosik, our physics teacher, suggested we read about Albert Einstein. “Art is the expression of the profoundest thoughts in the simplest way,” he is quoted as saying, handing me the key to many scientific puzzles and becoming a role model for life.

Guest “Artsbeat” columnist Paul Kando. (Photo courtesy Paul Kando)

I’ve spent my adult life doing research and engineering in several scientific and technical fields. Looking back, I realize that of all anyone has ever taught me, art education was the most important. Because, to quote Einstein again, “the value of an education in liberal arts is … the training of the mind to think of something that cannot be learned from textbooks.”

Freehand drawing and music were both required subjects in the Hungarian high schools I attended. One could not graduate without a decent grade in both, nor without knowing how to read musical notation and “solfege” hand signs that could teach a chorus to sing a new melody in no time.

“Language and Literature,” the study of artful communication and of belles-lettres – literary works valued for their aesthetic qualities – was another major subject. Poetry and its close cousin, the folk song, were much-loved elements of these studies. Foreign language classes (we had to have a working knowledge of at least two to graduate) also focused on belles-lettres.

Forget the contrived conversations of tourist language booklets – learn instead from Moliere in French, Dante in Italian, Tolstoy and Lermontov in Russian. Language, after all, is itself an art form of all peoples and cultures. Even in my old age (with languages long rusted by underuse), there is something magical about re-reading poems by Pushkin in Russian, Goethe in German, Virgil in Latin – and about getting with a Verdi aria sung in Italian and knowing enough Swedish to decipher Ibsen’s Norwegian while listening to Grieg’s “Peer Gynt” suite.

It was not just what we learned in art classes, field trips, and master classes taught by visiting artists and even whole orchestras, but how the other subjects were taught – about the music and rhythm of life in biology, the beauty of order in atoms and solar systems, the elegance of a math solution or a philosophical argument. This also acknowledged the importance of art in all human endeavors.

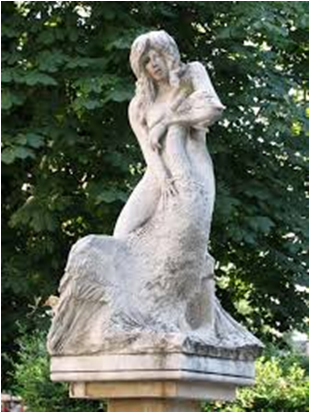

A close-up of the Kilus Fountain in Budapest, created by Paul Kando’s cousin, sculptor Miklos Melocco. (Photo courtesy Paul Kando)

Including statecraft. Regardless of the regime in power, the state was a major patron of the arts. By commissioning works of art in exchange for the artists sharing their work with farming villages and worker neighborhoods, the state made art less “elitist” and more accessible. Writers and poets got commissions to translate world literature. Theatrical performances and graphic arts exhibits traveled to local schools and community centers. Public sculptures sprang up on village greens and city squares, and at rural intersections – not to honor dead generals but to remind about favorite books, literary figures, and stories.

It is always a pleasure for me to discover some new “street sculpture” in Budapest, such as the dramatic “Empty Shoes” memorial to the Holocaust along the “Pest” bank of the Danube, and the bronze incarnations of the Paul Street Boys gang throwing dice in front of an apartment house on the actual Paul Street block, the scene (then an empty lot) of a beloved 20th century novel and silent film.

My sculptor cousin Miklos Melocco’s Kilus Fountain is a Greek-inspired marble ode to female beauty in my childhood neighborhood on Krisztina Square. A side figure of his King Mathias memorial in a provincial city bears the likeness of his father, my uncle Janos, a journalist executed for “spying” during the Stalin years. Art can be, indeed, both public and very personal.

The point of my art education was not for me to become an artist, but to become conversant with and enjoy the arts. Indeed, there is something wonderful about hearing a workman or farmhand whistle Puccini or Mozart instead of some pop song. The arts, it seems, are simply fundamental to being civilized.

Even more important is art’s release of hidden creative juices coursing in people’s veins. No matter how good engineers may be at their craft, their inner artist supplies the imagination for inventing innovative products and technologies. Art also arms us for survival when facing impossible odds: the loss of millions in gas chambers and gulags; the siege and carpet bombing of our hometowns; the rise, tenure, and inevitable fall of artless bores posing as saviors while looting our treasury; runaway climate change; and even the state murder of our innocent father.

Art elevates. It accounts for the difference between the female nudes of Manet, Goya, Titian, da Vinci, or Praxiteles, and those in “adult magazines” that discount women’s beauty in order to traffic in their objectified sex appeal. Art can turn a dull existence into vibrant living, politics into stewardship of the world. Art, my most important school subject, is, in Einstein’s words, “standing with one hand extended into the universe and one hand extended into the world, and letting ourselves be a conduit for passing energy.”

(Christine LaPado-Breglia is an award-winning journalist who has written about the arts in both California and Maine. Email her at clbreglia@lcnme.com or write her a letter in care of The Lincoln County News, P.O. Box 36, Damariscotta, ME 04543.)