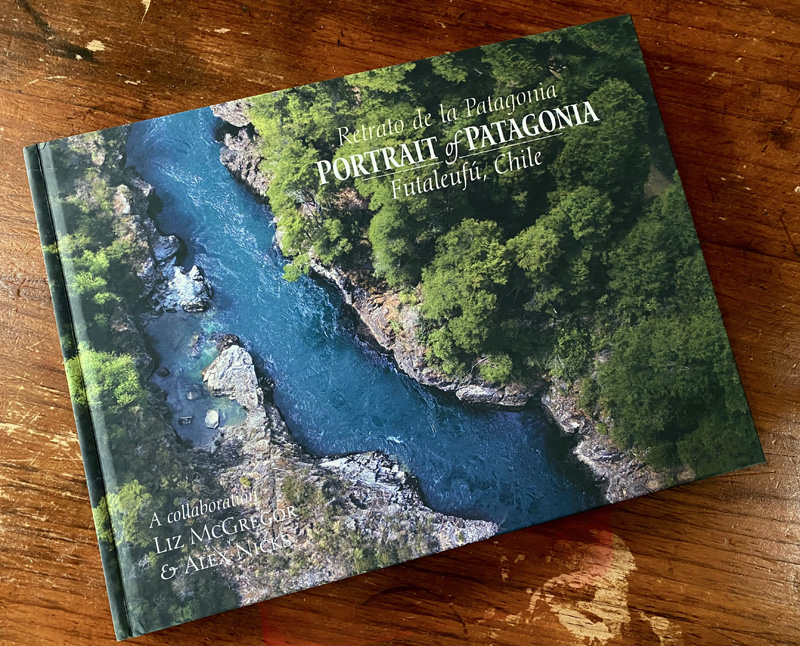

A copy of “Portrait of Patagonia – Futaleufu, Chile” rests on a table. Newcastle resident and visual storyteller Liz McGregor produced the book to share the scenery and culture of a place she considers her second home. (Photo courtesy Liz McGregor)

Newcastle documentarian and visual storyteller Liz McGregor published her first book, “Portrait of Patagonia – Futaleufú, Chile,” about the place she considers her southern home on Oct. 1.

She calls it “a love letter to Futaleufú… a hand-held tour to the places and faces of, in my opinion, one of the most beautiful spots on the globe.”

The coffee table book is collaboration between McGregor and National Geographic photographer Alex Nicks. Together they captured the stunning drama of the Futaleufú River and created a record of its culture and community.

Visual storytelling is McGregor’s calling, she said, and environmentalism her passion. She spent much of her career melding the two, looking for a way to graft her love of the natural world onto projects to reach an audience, to educate, entertain and inspire.

McGregor worked on documentaries and independent feature films, directed film festivals, and conceived and created film and video content through her own production company BoonDocs, so named, she said, because a boon is a blessing, something good.

McGregor’s roots in filmmaking started young when she used her father’s video equipment to make brief betamax movies.

The focus on environmentalism came a little later, near the end of her stint as a theater major at Wittenberg University in Ohio.

“I needed to shake myself up a bit,” she said.

She spent a semester in the southernmost part of South America with the National Outdoor Leadership School, a program she likens to Outward Bound. There in Patagonia she spent three months hiking, kayaking, visiting the fjords, and exploring the ice fields.

That formative experience cemented a connection to the outside world that continues to inform her choices – what she creates, where she lives.

“Everywhere we live we’re on a river,” she said. The Marsh River, a tributary of the Sheepscot, runs behind her Newcastle home.

“Being close to the water is what drew us here and to this property. Wild spaces in the suburbs are hard to find,” McGregor said.

Another river, the Futaleufú, continues to draw her back to Patagonia.

McGregor and her husband, Alex Obregon, an international adventure guide, met on the Futaleufú. They own land in the river valley and return annually to a place with no internet, no electricity.

“It’s like going back in time, more horses than cars,” she said.

Liz McGegor opens her book “Portrait of Patagonia – Futaleufú, Chile” to a favorite page at her home in Newcastle on Wednesday, Oct. 6. Some of the most dramatic photos were taken during rafting and kayaking tours of the Futaleufú River. (Bisi Cameron Yee photo)

At one point McGregor saw herself making Patagonia her final home. But being there during COVID, unable to fly back to the states, forced to stay till the beginning of winter despite being unprepared for the harsher aspects of the climate, realizing that the local hospital only had a single respirator gave her pause.

When travel restrictions were finally lifted, she was relieved. “Coming home to Maine felt so good,” she said.

McGregor worked on “Portrait of Patagonia” for seven years. “The first time I printed it, it looked like a Shutterfly book,” she said.

But she continued to refine it, to add pictures, to add text. She included portraits of the people, and shots of local events to flesh out the narrative. She made sure the book was bilingual so that it is accessible to the people she photographed.

McGregor doesn’t call herself a photographer. She admits she isn’t trained in the mechanics of apertures and shutter speeds. But she knows how to obtain the results she wants from a camera or drone. Or from an iPhone which is what was used to capture the spectacular sunset images in the book.

“Looking through photos you get an emotional reaction,” she said. She wants people to turn the pages and be transported. To see the vivid blue of the river, the blue that she calls “Tupperware turquoise” because the color is so bright it almost seems unnatural.

She wants them to see the sun striking off the ice on the mountains, the deep greens of the vegetation in the valleys, the welcoming faces of the local people, the steam rising from the food.

“Perhaps you’ll want to visit,” she said. “Perhaps you’ll want to protect it.”

Things are changing in Patagonia. The internet is coming, bringing access to a better life for the people there. McGregor knows they want that, but her protective instincts cause her to worry about the cost to the pristine land, to the delicate balance of life along the river’s edge.

“It’s hard to ask people to care for things outside their local scope these days,” she said. But people who have not had the opportunity to experience other places, other cultures might be interested in this intimate look into life in this valley and this place that is still wild, still clean, still spacious.

“It feels vast,” she said, of Patagonia. “You can stand and look up the valley into the glacier. There are landslides, volcanic eruptions. It’s unpredictable. You just feel so alive. It’s like resetting your whole being.”

“Portrait of Patagonia – Futaleufú, Chile” is currently available at portraitofpatagonia.com and will be available at Sherman’s Maine Coast Book Shop in Damariscotta in November.