Brian Beal, a professor of marine ecology at the University of Maine at Machias, presents the results of an experiment on the Bremen clam flats. (Alexander Violo photo)

A 2019 experiment on the mud flats of Bremen’s Broad Cove did not show any benefit from “brushing” or “netting” techniques for clam populations, likely as a result of water temperatures and booming predator populations.

The traditional technique of brushing slows down currents and allows juvenile clams to settle, but also appears to create ideal habitat for predators like green crabs and mummichogs. Netting, meanwhile, protects juvenile clams from predators, but does not attract juvenile clams to settle in the protected area.

“If we did this study in 1968, I think it is going to work. There were no green crabs around because it was so cold,” said Brian Beal, a scientist with the Downeast Institute and professor at the University of Maine at Machias.

Beal presented the results of the experiment to the Bremen Shellfish Conservation Committee on Thursday, Jan. 9.

Local shellfish harvesters partnered with scientists from the Downeast Institute to conduct the research from May until they retrieved samples of mud from Broad Cove at low tide Nov. 1, 2019.

Brushing involves the insertion of tree boughs into mud flats to reduce currents and encourage settlement of juvenile clams. Shellfish harvesters along the Maine coast employ the technique.

“While brush may enhance juvenile clam density initially, it cannot protect settling clams from predators,” Beal said.

According to Beal, the results of his large-scale research suggest that brushing may work with colder water temperatures. But with warmer water temperatures, invasive green crabs and other predators may use the brush as habitat and focus their predatory activities on the brushed areas.

“They can have a ‘crab hotel effect,’ providing predators an ideal habitat,” Beal said.

Shellfish harvesters and scientists braved strong winds and thick mud to pull 180 “benthic cores,” or samples, and 54 recruitment boxes out of Broad Cove on Nov. 1, using jet sleds to haul them out of the mud and onto the shore at the Hay Conservation and Recreation Area.

“Recruitment boxes yielded few clams, but enough so we know that clams settled to the flat during the time between May and October,” Beal said.

The experiment was part of the first study into the effectiveness of brushing on clam recruitment and survival throughout the Maine coast, with similar experiments conducted in Gouldsboro and Harpswell.

“Objects such as brush that create some resistance to tidal or wind-driven currents enable clams that have settled onto the flat to remain within the shadow or halo of those objects,” Beal said.

Beal said the Bremen results suggest that brushing does “baffle,” or slow down, currents. This creates the opportunity for clams to settle.

“Whatever baffling occurred around the brushed plots did not translate into more clams in those plots. No significant effect due to brushing was observed in this study,” Beal said.

“Unfortunately, at a time when seawater temperatures are increasing along with predators, the objects, such as brush, also tend to provide habitat for predators, such as crabs and bottom-feeding fish, such as mummichogs,” Beal said.

In addition to brushing, Beal’s experiment deployed nets to protect clams from predators.

“Netting also did not result in an enhancement of wild juvenile clams,” Beal said.

Beal explained that the densities of juvenile clams did not differ significantly between the experiment’s brushed and netted plots. The experiment’s control plots of unaltered mud had more clams than the plots that received brush.

“Depending on mesh size, netting can provide a certain degree of predator protection to small clams, but netting does not attract clams. It only protects what settles,” Beal said.

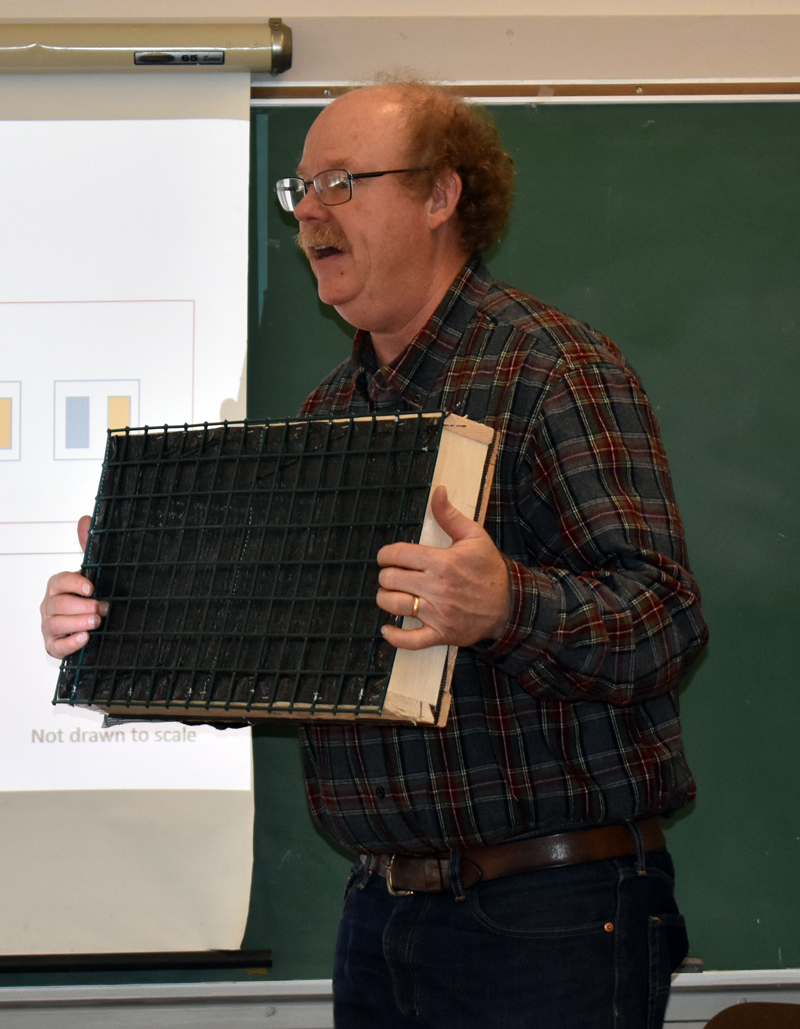

Brian Beal, a professor of marine ecology at the University of Maine at Machias, holds up a clam “recruitment box” during a presentation at the Bremen town center Thursday, Jan. 9. (Alexander Violo photo)

Local shellfish harvester Jeremy Prior, who said his family has been harvesting clams for several generations, asked if clams can tolerate the warming water temperatures in coastal Maine.

According to Beal, warmer water itself does not present a problem for clams. The soft-shell clam’s range extends from the Chesapeake Bay to the Canadian Maritimes and the species grows well in a warm environment. However, populations of predators such as green crabs can boom as temperatures warm.

Pryor asked if Beal had studied the characteristics of mud in clam flats to see if that impacts clam populations.

Beal said he hopes to test mud in future experiments, paying particular attention to levels of acidification.

Pryor asked about putting old clam shells on the flats to attract clam settlement.

Beal said his past experiments have not proved the effectiveness of this traditional method.

Pryor said the prevalence of predators is making it difficult to understand the results of experiments. Beal agreed.

Funding for the study came from the Maine Shellfish Restoration and Resilience Project, the Broad Reach Fund, and Maine Sea Grant.

Beal wants to conduct more experiments in Bremen in 2020 and 2021, in addition to experiments up and down the coast, to further investigate clam recruitment techniques, including the use of recruitment boxes.

Beal said the future experiments will not involve brushing. The next series of experiments will take place in nine towns, with two locations in each town, for a total of 18 sample areas.

“The recruitment boxes are designed to see what is settling out of the water, what the differences are region to region, flat to flat, collecting information on clam recruitment to see how it differs,” Beal said.

Selectman Boe Marsh said Beal’s experiments will survey two locations in Bremen, potentially in areas of Broad and Greenland coves.

Beal said he wants to draw attention to the trying circumstances currently facing Maine’s shellfish industry. He said soft-shell clam landings in Maine have declined by 45% since 2001.

“This project aims to increase public awareness of what is occurring within this iconic fishery. We wish to create a statewide data set for fisheries managers in (the Maine Department of Marine Resources) and for other fisheries scientists to better understand factors that affect the health and well-being of the fishery,” Beal said.

Another goal of the studies is to work with coastal and island schools to have students help monitor area clam populations, according to Beal.