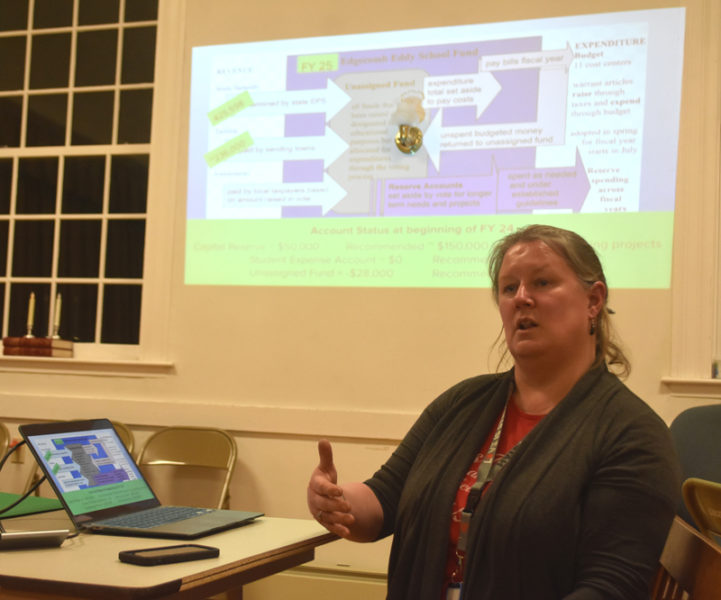

Edgecomb School Committee Chair Heather Sinclair explains the education budget’s revenue sources and expense categories at a joint meeting with the towns budget committee on Wednesday, Feb. 28. Sinclair said Edgecomb Eddy Schools increasing need to raise funds through taxation is the result of issues in state policy and formulas, and asked all in the room to join her in asking for change in Augusta. (Elizabeth Walztoni photo)

The Edgecomb Eddy School has long been recognized for its educational quality, but making the numbers work has been a challenge for years, and this budget cycle is no exception.

The school committee voted unanimously on Monday, March 4 to recommend a $3,760,261 education budget, an increase of $344,096 or 10.07%, with $3,098,672 to be raised through taxation. If voters approve it in May, education taxation will increase by $551,072, or 21.21%.

Members of the school and budget committees agreed at a joint meeting on Wednesday, Feb. 28 that the amount – accounting for unexpected needs and the requirements of state statutes – could not be reasonably reduced.

“If we asked you to cut $250,000, I think you’d be hard-pressed to find it without crippling the school,” budget committee member Joe McSwain said at the end of the two-hour meeting.

The Edgecomb Eddy School educates 103 students from prekindergarten through sixth grade, a handful of which are tuitioned nonresidents. Edgecomb students have school choice for middle and high school.

Edgecomb is part of AOS 98, which also consists of Boothbay-Boothbay Harbor, Georgetown, and Southport.

Boothbay Region High School Principal Tricia Campbell, who attended the meeting, said other members of AOS 98 are seeing “broad increases across the board” as their budgeting processes progress.

In Edgecomb, regular instruction totals $2,181,157, an increase of $142,012 or 6.96%, and special education runs $731,020, an increase of $163,129 or 28.72%.

Aside from special education, this year’s cost increases are concentrated in contractually required salaries and benefits, along with the purchase of a new school wide literacy program to replace one out of date.

The estimated $10,000 difference in overall cost per student between Edgecomb and the Boothbay-Boothbay Harbor Consolidated School District, also part of AOS 98, would be nearly the same if the needs of their student bodies were distributed differently, according to School Committee Chair Heather Sinclair.

Special education costs in particular, which the town legally must provide under state law, run well over $100,000 per student per year.

Elsewhere in the budget, student and staff support totals $110,460, an increase of $7,533 or 7.31%, and transportation and buses $100,317, an increase of $17,810 or 21.58%.

Costs decreased in the system administration budget to $123,554, down $6,681 or 5.12%, due to a reduction of the AOS 98 central office budget approved last week.

On the revenue side, projected state subsidy is down to $425,589, a decrease of $56,976 or 11.8%, due in part to the town paying off its building debt two years ago and shifts of state calculations.

Tuition income from nonresident students remains stable, but combined with drained reserve accounts and the end of federal pandemic relief used to offset taxes, $661,589 of revenue is expected in total this year. The committee used those sources to offset taxation in past years, but now have neither to work with.

Edgecomb Budget Committee Chair Jack Brennan (right) discusses concerns about burdens on taxpayers as member Stein Eriksen listens during a joint meeting with the school committee on Wednesday, Feb. 28. While the budget committee concluded the projected $3.76 million education budget could not be further cut without “crippling” the Edgecomb Eddy School, members expressed concern about future financial sustainability if the percentage of the budget raised by taxation continues to increase. (Elizabeth Walztoni photo)

The last two years “were a textbook reason why you have reserve accounts,” according to Sinclair. Unexpected student costs the town was legally obligated to meet arose in 2022, and the next year the well at Edgecomb Eddy School failed.

Without money in reserves, the school committee might face calling a special town meeting to raise more money through taxes midyear if unexpected costs arise or if the budget is voted down at annual town meeting.

Next year’s budget will likely include repaving the school’s driveway. The committee expects it to cost over $100,000 and held off this year to see if it could be added to the town’s municipal paving schedule.

With all of these costs in mind, committee members said Feb. 28 they were at a loss to reduce taxation without a change in state operations.

Maine funds public schools through its essential services and programs formula, which determines the minimum contribution from the state and towns to provide basic education. Each town’s ability to pay is assessed in part by property value, and the state distributes subsidy from there based on calculated need, broadly speaking.

Sinclair estimated subsidy covers about 19% of needs in Edgecomb, contrasting with 80-90% in other towns. With waterfront property on two sides, Edgecomb is assessed with a higher ability to contribute.

Basing taxes on property values in a state that is rich in land and low in income is a fundamental issue, in Sinclair’s view. She has gone to Augusta herself asking for help, she said, and encouraged those in the room to join her.

“We in this room can’t fix that,” she said. “We need to yell at other people.”

With these factors considered, the school committee believes the measure of financial viability is the percentage of Edgecomb’s taxes going to education. Last year, education expenses made up 58% of the tax bills. The committee aims to keep it under 60% long term.

Members of both committees hoped an upcoming town revaluation would provide more funds and “change the conversation,” though others doubted it will.

The budget committee did not dispute any presented costs this year, but Chair Jack Brennan said the school should develop a long-term plan to assure residents that double-digit percentage increases in taxation won’t continue.

Brennan noted the town has other expenses that are based on property valuation, such as the ambulance service and the transfer station, and raised concerns about the overall municipal budget.

“I just don’t see how it’s going to work, and I’d hate to see it on my shift that we start talking about whether we can have a school,” he said.

Residents have sometimes asked to close the school for years, even before the new school building opened in 2002, according to Lincoln County News archives. Town officials met with legislators to ask for more state funding for education expenses in 2017, a particularly contentious budget year.

If the school closed, Edgecomb would be responsible for tuitioning its students elsewhere, which committee members said might mean a different kind of bad news – a loss of local control, responsibility for an unused building, and uneven reimbursement by the state.

Select board member Lynn Norgang, who was in attendance at the meeting, said residents have commented to her that the school committee appears to ask for the “best of the best” each year and presents it as nonnegotiable.

“This is the bare bones budget,” Sinclair said, adding that she welcomes suggestions on communicating it.

The school chooses to spend more on its teachers than surrounding towns, but faces mostly fixed costs, according to Sinclair. Tuition, maintenance, and state-mandated services are outside the town’s control.

Those in attendance Feb. 28 agreed a change in messaging was needed to make clear what the school committee was asking for.

“We need to communicate it that way to keep the school here forever,” Norgang said.

AOS 98 established a long-range planning committee last year to discuss the future of the school system. Sinclair said public participation has been low, and they welcome ideas from residents.

“I would love to have a conversation about it,” she said.

Edgecomb residents will vote on the budget at annual town meeting Saturday, May 18 in the town hall. School committee members plan to have handouts available explaining the budget.

The committee’s next regular meeting begins at 6 p.m. Monday, March 11 at the Edgecomb Eddy School and on Zoom. Members plan to include an agenda item to discuss public engagement ideas around the budget vote.

For more information, go to aos98schools.org.