Waldoboro resident and historian Michael Amico (right) sifts through soil removed from his property in fall 2023 while archaeologist Harbour Mitchell looks on. “Waldoboro could become a go-to place for science,” Mitchell said on Jan. 28. (Photo courtesy Michael Amico)

To archaeologist Harbour Mitchell, every fragment of pottery tells a story – and in Waldoboro, he said, the earth is dense with stories like nowhere else in Maine.

“Now this – this was a tea bowl,” Mitchell said on Sunday, Jan. 28, retrieving a 1-inch piece of stoneware from a plastic specimen bag and laying it on the wooden surface of a dining table in his Waterville home.

The fragment, found in a backyard in Bremen, was smooth, thin, and subtly curved, made of white stoneware with a delicate slip glaze. It measured only about 1 inch long, but observations of the piece’s slight curvature, materiality, and thickness were all that Mitchell needed to fill in an approximation of the original vessel in his mind’s eye.

This is the basic act of Mitchell’s work as an archaeologist in Maine: searching for fragments of history in the area’s soils, then going about the in-depth work of piecing together the stories that the unearthed artifacts contain.

Together with other local historians, Mitchell has proposed to the Waldoboro Select Board that the town form a dedicated archaeology committee to help residents discover and engage with the town’s rich and uniquely accessible cultural history.

Mitchell’s research has taken him across the Midcoast over the past 30 years, with the artifacts and sherds – spelled with an “e” when referring to stoneware, unlike glass “shards,” Mitchell noted – in his collection hailing from Belfast, Thomaston, and the St. George River, among other locations further afield.

But after spending the last three years excavating sites in Waldoboro and studying the area’s history, Mitchell said he does not know of anywhere else in the state that compares to the town in terms of archaeological site richness and diversity.

“The circumstances (in Waldoboro) are just so unusual as to be near-unique,” Mitchell said Jan. 28.

Those circumstances include a confluence of cultural factors, including the social class and occupation of residents and pressures on early settlers from conflicts like the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which ultimately caused different groups to settle in different areas at different times, Mitchell said.

This has resulted in the land that is now Waldoboro being strewn with relics from different time periods. Artifacts from those various eras are concentrated together, affording archaeologists greater clarity and confidence about the historical context of the pieces they excavate, Mitchell said.

By comparison, he said, settlements elsewhere in Maine were regularly built in the same place one after another, causing the remnants of structures and people who came before to be lost.

“Everything is built on top of something else,” Mitchell said.

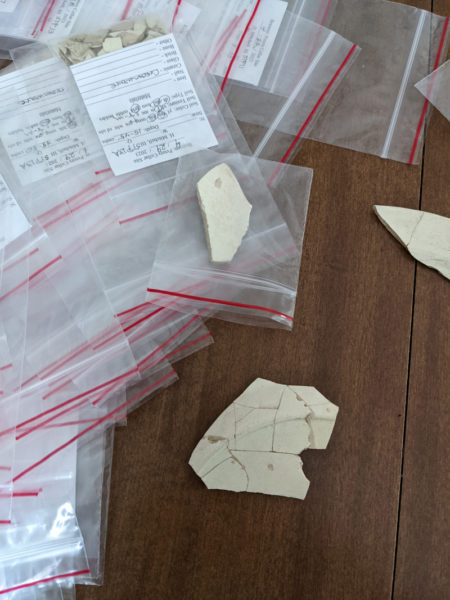

Fragments of stoneware lie in an excavated pit on land belonging to Waldoboro residents Conrad Winslow and Michael Amico in fall 2023. Similar artifacts, as well as building foundations, garrissons, tools, and personal effects of settlers dating back to the 1700s are present at archeological sites across Waldoboro, according to archeologist Harbour Mitchell. (Photo courtesy Michael Amico)

While Mitchell noted that Waldoboro’s archaeological sites are readily accessible, often located only inches beneath the topsoil, he also acknowledged that this makes the sites vulnerable to being disturbed before they are ever found and studied.

Development could compromise archaeological sites in town, Mitchell said, speaking before the Waldoboro Select Board at its meeting on Jan. 23 with Waldoborough Historical Society President Bill Maxwell and resident and historian Michael Amico.

“If five to 10 years from now nothing is done, and more and more houses are built, this will be gone,” Mitchell said.

“What we want is to act before it’s too late,” Amico added. “With increasing development … we will very, very quickly lose this opportunity,” he said.

Amico, Maxwell, and Mitchell shared their vision for a town committee that could help residents discover and engage with the archaeological history on their property.

A dedicated committee, they said, could help to spread the word about the unique archaeological opportunities present in Waldoboro and provide a framework for landowners who may be curious about what is beneath the surface of their own land to begin to unearth its secrets.

Amico said he hoped that excavating physical evidence of times past could make previous inhabitants of Waldoboro feel more real, helping modern-day residents connect with their predecessors.

“By getting to the remains, we can begin talking about experiences, what people did in their daily lives and even what they felt,” Amico said on Jan. 23. “Anger, fear, joy, pride – basic emotions that shaped the lives of the earliest settlers of this area, and that I would argue still shape people in this place today.”

“I don’t think a community can know who it is until it knows who it was,” Mitchell said.

Unearthing the town’s archeological history, he added, may help illuminate the history of Waldoboro’s other cultural groups, including those whose histories are less often retold in town history books, such as enslaved Africans and Indigenous Americans.

If an archaeology committee is formed, Mitchell said it would be “critical” to ensure that Penobscot or other Wabanaki individuals are represented among its members. Mitchell said that pre-colonial archaeological sites in Waldoboro date back as far as 11,000 years ago.

Revealing the complexities of intercultural relationships that have existed for centuries in Waldoboro, Mitchell hopes, could add more dimension to residents’ understanding of what it means to live in Waldoboro. However, one obstacle to this effort is the fact that most of Waldoboro’s archaeological sites are located on private land, he said.

In his previous work, Mitchell said that the need to coordinate digs with landowners has been a positive, helping foster relationships and start one-on-one conversations with land stewards. Almost always, he said, landowners are curious to discover the history of their property. The artifacts that Mitchell finds during his digs remain in the possession of the landowner, he said.

Carefully labeled and catalogued, fragments of stoneware from a Bremen dig site lie on the dining room table of archaeologist Harbour Mitchell. The green cast visible on the pottery at bottom, Mitchell said, identifies the piece as “creamware,” a type of pottery produced in the late 1700s and 1800s. (Molly Rains photo)

However, Mitchell, Amico, and Maxwell believe that the unique archaeological opportunities present in Waldoboro call for a greater level of infrastructure to help engage local landowners and add to the community’s understanding of its history.

“Everything grassroots has to eventually become formalized so that it lives on … at some point, the town has to take ownership,” Mitchell said on Jan. 28.

At the Jan. 23 meeting, Amico, Mitchell, and Maxwell asked that the town consider putting an ordinance detailing the formation of the committee on the town warrant for the spring town meeting.

“We want to create town buy-in and awareness of this project,” Amico told the select board.

Amico said he hoped that Waldoboro could function as a model for other communities that hope to undertake similar explorations of their shared history – and, in doing so, help to strengthen the town’s community.

The Waldoboro Select Board may opt to bring the article to town meeting, go ahead with creating the committee without bringing the article to vote, or opt not to pursue either option. No movement has yet been made in regard to the proposed committee, but board members said they would continue to discuss it at their next meeting on Tuesday, Feb. 13, at 6 p.m. in the Waldoboro municipal building.

“I think this could be the beginning of the writing of a new communal history,” Amico said.

“The potential here is enormous,” Mitchell added. “We’re stewards of all of this.”