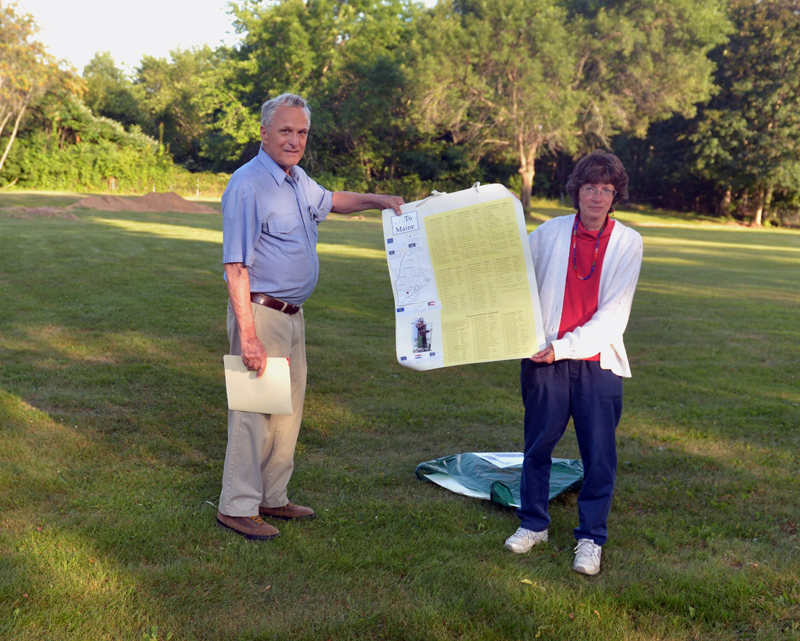

Ed Greiner and Ann Cough stand on the section of Plaisted Cemetery in Gardiner where they say 262 people were buried in unmarked graves, including at least 27 from Jefferson. They have spent countless hours researching the burials at Plaisted Cemetery and other unmarked graves in the Gardiner area. (Paula Roberts photo)

A Gardiner researcher says hundreds of people, including veterans and residents of the Old Men’s Camp in Jefferson, are buried in unmarked graves in area cemeteries.

Ann Cough has conducted extensive research on cemeteries in Gardiner and Pittston and discovered that 262 people are buried in unmarked graves at Gardiner’s Plaisted Cemetery alone, including 27 from Jefferson.

Cough and friend Ed Greiner have spent countless hours combing through town records and going through documents and microfilm at the Maine State Library and Maine Law Library.

Cough has spent the past 30 years researching genealogy. She became interested in local cemeteries while placing flags and later wreaths on veterans’ graves in the Gardiner area.

An ancestor, Civil War veteran Thomas Doyle, is buried in Plaisted Cemetery. Her research on Doyle led to the discovery of the unmarked graves.

“They are buried like sardines,” Cough said of how closely the dead were packed together at Plaisted. “I consider (them) recent deaths. This was not 1842, it was 1942. Some were loggers and woodsmen with no families they could go live with.”

There are no burial markers and no signage to tell what lies below their grass-covered graves, located just beyond a row of trees on West Hill Road in Gardiner. The grassy field has not had a burial in “well over 50 years,” Cough said.

Mostly men were buried at Plaisted Cemetery, with a few women, Cough said. “They were born all over the country and the world, as far away as Russia, Germany, and Ireland,” she said. Sixty-four were born in the U.S., the rest in other countries. Many were state wards.

Two hundred were buried at Plaisted Cemetery between 1942 and 1952. Another section holds the remains of 62 others who found their final resting spot from 1952-1957. A fence separating the two plots was recently removed by the town of Gardiner, which maintains the property.

“Two men we know of were veterans,” Cough said. Their grassy burial grounds stand out in stark contrast to the memorial stones next door, which date back to the early 1800s and include monuments to many Civil War dead.

“A lot of them were considered paupers,” Cough said of the men buried in the field.

Cough said there are also unmarked graves at St. Denis Church’s Calvary Cemetery and Pittston’s Riverside Cemetery, by the Colburn House School. An unassuming wooden crucifix marks the spot at Riverside.

“Without a grave marker, who knows how many?” she said. “Who would have paid for a marker?”

She said it is “hard to figure” how many residents of the Old Men’s Camp have been buried in the unmarked graves. She found an obituary and death notice for a Peter Granatick (also spelled Granatich or just Grant), of Jefferson, one of the 262 buried at Plaisted. “His obit says he was buried in a family plot. It sounds nice, but it is not true,” she said.

The city of Gardiner has a list of the names of those buried in the unmarked graves, with their dates of birth and death, birthplace, and two initials after that.

“I figure the initials were for the funeral home,” Cough said. Many were residents of area nursing homes, including Willowcrest Nursing Home, of Pittston; and Merrill Manor and Robinson Resthome, of Gardiner.

The Old Men’s Camp in Jefferson started out as one of many Civil Conservation Corps camps across the country, part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal in 1933. The CCC was an effort to put young men to work during the Great Depression after World War I.

A field at Plaisted Cemetery in Gardiner has no stones to mark the remains of 262 people, including 27 from Jefferson, according to local researchers. (Paula Roberts photo)

There were two companies housed in Jefferson, the 389th Bonus Veteran Company (1933-1935) and the 1163rd P51 company (1934-1940). The Maine Forest Service was the supervisory agency for both companies.

After the Depression, “There was a crisis in the state,” Greiner said. “There were too many old men with no place to put them, so the state started the camps.” Greiner joined Cough in her research six years ago.

The federal government gave the state the 10-acre CCC camp, at the current site of N.C. Hunt Lumber in Jefferson, for an experimental Old Men’s Camp for elderly men without families. At the time, the state was spending $150,000 a year to support 200 men, many of whom were former loggers.

Charlie Brown, Maine’s director of general relief, told The Saturday Evening Post of “200 down-and-out old men” being installed at the camp. “These men were at the end of their ropes,” he told the magazine.

The day after the camp’s first residents arrived, Brown arranged for young carpenters to go to the camp and make repairs, but the old men would have nothing to do with it. They wanted to fix up their own homes.

“They came in yesterday, not caring whether they lived or died. Now they’re as cocky as a bunch of bantam roosters. It was the first sign the camp would be a success,” the article reported.

The men soon worked themselves out of a job and became restless. They started talking about raising vegetables and chickens and other farm animals. Sensing the success of its experiment, the state bought a neighboring 40-acre farm and 125-acre wood, and the old men set to work.

“We told them to go ahead and raise any danged thing they wanted to, up to and including watermelons and elephants,” Brown said in the article.

The men set to work, reading seed magazines and articles about raising farm animals. They raised much of their own food and reduced the state’s cost to care for them from $150,000 a year down to $48,000.

In October of every year, pumpkins grown at the Old Men’s Camp were loaded onto an old truck, driven door to door, and given away to the children in Jefferson.

The Jefferson history volume “Touchstones I” refers to the facility as the Health and Welfare Camp and says it was established in 1942 to provide homes for elderly and disabled men.

The state closed the camp in 1970 and Forrest Hunt, of Newcastle, bought it, according to “Touchstones I.”

Cough is worried that as time marches on, those buried in unmarked graves, like the 27 from Jefferson at Plaisted, will be forgotten. She has made it her mission to make sure people do not forget.

“Most people would not know,” she said. “There is no way they would know.”

“It is not right to have 262 buried here with no marker. Most (people) have no knowledge of who is buried here,” Greiner said.

“She hates to see kids playing football here,” Greiner said of his fellow researcher.

“People should know it is not a playground,” Cough said. “This seemingly unused grassy field next to Plaisted Cemetery is, in fact, a cemetery. It is time to mark these graves with a suitable plaque or stone.”

“I regret that we do not have a granite monument to let people know this is a cemetery, that this is not just empty land, that this is not a mistake where they just dumped bodies, that the state of Maine was doing something to take care of them,” Greiner added.

“They all had their stories. I have been and will continue to investigate their lives, person by person,” Cough said.

Anyone interested in helping Cough with her project may contact her at 582-2823.