From left: Martin Luther King Jr. Day event organizers and speakers Lindy Gifford, Rev. Allison Smith, Rev. Mike Stevens, Rev. Mark Hamilton, Reza Jalali, and Rev. Erika Hewitt gather around the People United Against Racism banner at The Second Congregational Church in Newcastle on Monday, Jan. 16. (Abigail Adams photo)

Leaders of several religious faiths gathered at The Second Congregational Church in Newcastle on Monday, Jan. 16 for a celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The interfaith event was dedicated to building the “beloved community” King often referred to as the end goal of the non-violent actions he led during the civil rights movement.

Representatives of Judaism, Islam, and Baha’i, as well as the Congregationalist, Quaker, and Unitarian denominations of Christianity, participated in the ceremony. About 150 community members filled the sanctuary to sing, pray, and listen to the words of members of other faiths.

The ceremony was “modeling diversity,” said the Rev. Erika Hewitt, minister of the Midcoast Unitarian Universalist Fellowship in Damariscotta and organizer of the ecumenical grass-roots group People United Against Racism, the sponsor of the event.

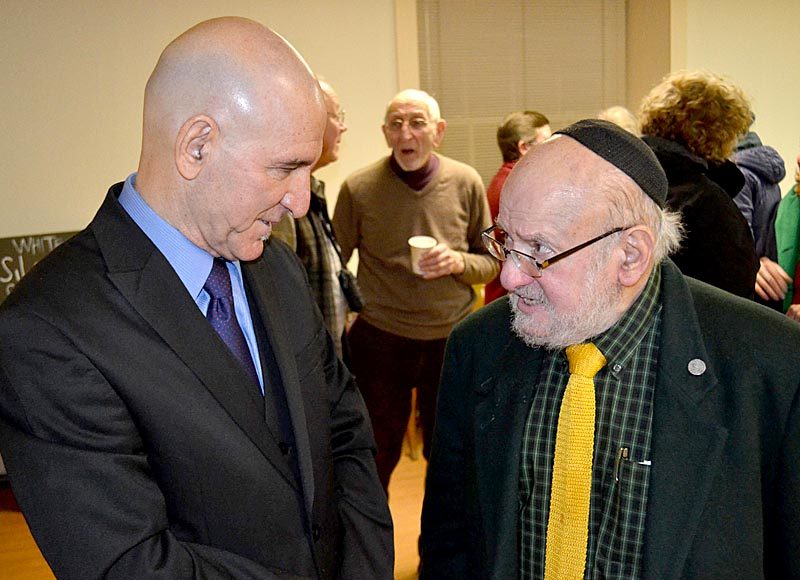

Reza Jalali (left) and Rabbi Steve Shaw speak after a Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration at The Second Congregational Church in Newcastle on Monday, Jan. 16. (Abigail Adams photo)

The organizers invited Reza Jalali to give the keynote address. Jalali is a former political prisoner and refugee, an award-winning writer, and a human rights activist. He serves as the Muslim chaplain at Bowdoin College, teaches Islam at the Bangor Theological Seminary, and is the coordinator of multicultural student affairs at the University of Southern Maine.

Jalali apologized to the audience at the outset of his speech for being “too political” before going on to speak of the fear that has gripped him, as a Muslim-American, since the election of President-elect Donald Trump.

Jalali came to the U.S. as an Iranian refugee fleeing persecution after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. He became a U.S. citizen and has lived in Maine for the past 30 years.

“The day after the election, I started to look over my shoulder,” Jalali said. “I felt like a ghost, a stranger in a land that had been familiar to me the day before.”

Trump’s campaign rhetoric in regard to Muslims and refugees was “very personal for me,” Jalali said. Jalali’s speech at the event constituted “his personal tale of grief,” he said.

His grief “was not about the outcome of the election,” Jalali said. “This grief is about my fellow Americans turning on each other.”

As a man who came to the U.S. to flee persecution and tyranny in his native country and raise a family with dignity, Jalali said he now fears for the safety of his daughter, who joined protest marches after the Nov. 8 election.

“She was a brown face in a sea of white,” Jalali said. “She looked so vulnerable.”

As a human rights and refugee activist, Jalali said he thought of the Syrians seeking safety and shelter from the civil war that has destroyed their country. “We turned our back on refugees,” Jalali said. “Many of them will perish.”

Jalali is no stranger to the politics of division, he said. As a member of the board of directors of Amnesty International USA, Jalali led delegations to refugee camps in Bosnia, interviewing and compiling the stories of survivors of the ethnic cleansing of the Balkan War of the 1990s.

The story of each refugee followed a similar theme, Jalali said. For generations, the ethnic groups in the Balkans lived as neighbors, but the politics of division tore them apart.

Political leaders pitted one group against the other, and neighbors in what was formerly a shared society began to kill each other, Jalali said.

“There are questions in front of us,” Jalali said. “Will we go back to the days of illegal abortion shops, hangings, internment camps, blacklists?”

The U.S. was the country that brought the world Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Jalali said. The social gains made by the civil rights movement are being drowned out by finger-pointing, accusations, and scapegoating, or “the politics of division,” he said.

Jim Matlack, clerk of the Midcoast Friends Meeting, lobbied to have Martin Luther King Jr. Day recognized as a national holiday. (Abigail Adams photo)

Jim Matlack, clerk of the Midcoast Friends Meeting, heard King preach in the late 1950s, marched on Washington in 1963 when King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, participated in several actions throughout the civil rights movement, and “felt the shock of King’s assassination,” he said.

Matlack worked with his fellow Quakers to lobby in Washington, D.C. for Martin Luther King Jr. Day to become a national holiday, a process which took 15 years, he said.

“We will need courage in the times we are facing to act as our faith calls us to do,” Matlack said.

While large-scale political activism such as protest marches are important, the most important decisions people will make in how to handle the controversies facing the nation will be the decisions people make in the course of their daily lives, he said.

The gains of the “beloved community,” a global vision of humanity living free of poverty, hunger, homelessness, hatred, and bigotry, which King often said was an attainable goal, “will be in the fabric of how we live our life every day,” Matlack said.

To continue to build the “beloved community,” The Second Congregational Church and People United Against Racism will hold a series of discussion groups over the next month. Many attendees signed up for the groups after the ceremony.

Attendees of a Martin Luther King Jr. Day event at The Second Congregational Church in Newcastle hold hands while singing “We Shall Overcome.” (Abigail Adams photo)

Topics of the group discussions will include the Black Lives Matter movement, intergenerational and historical trauma, tolerance education, white privilege, the impact of slavery on American culture, and book and documentary film discussion groups.

The discussion groups are “a tangible way” the community can gather together, dismantle racism, deepen their fellowship with each other, and continue to work toward strengthening the “beloved community,” said the Rev. Allison Smith, interim pastor of The Second Congregational Church.

The very presence of the community members and speakers who turned out for the event is in itself a demonstration of the community’s commitment to King’s vision, Smith said.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration was a first-of-its-kind interfaith event in Lincoln County, Smith said. “To that, let us say ‘Amen.’”

For more information about the community discussion groups, contact Shirley Tawney at 563-5471 or stawney@twc.com.