The sign marking Peterborough Cemetery in Warren. (Anna M. Drzewiecki photo)

“A quick scan through old local censuses confirms that we have centuries of Black history in our county to learn more about,” said Executive Director of the Lincoln County Historical Association Shannon Gilmore.

In honor of Black History Month, the LCHA arranged a two-part lecture series addressing the presence of Black history in Lincoln County and, more generally, the Midcoast region.

“I am very excited that Bob Greene and James Tanzer both agreed to join us for a talk this month as we celebrate Black history month,” said Gilmore.

On Feb. 10, historian and journalist Bob Greene presented his lecture “Black History of Maine” online with attendance by donation.

The online description to his lecture reads: “It is frequently said that Maine is the whitest state in America. Yet Black people have a long history in the Pine Tree State. Slaves? Yes. But also builders, farmers, fishermen, ship captains, educators, etc.”

Greene, whose family has lived in Cumberland County for eight generations, started researching Maine’s Black history through genealogy; since then, he has learned and taught extensively on the issue and, in 2021, received the Maine Historical Society’s Neal Allen Award.

The second lecture, delivered by James “Jamey” Tanzer, will take place Feb. 24. Tanzer, a member of LCHA’s board of trustees, is an independent researcher and Museum Outreach Coordinator at Bowdoin College’s Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum.

He is also a member of the Maine-based Atlantic Black Box Project, a collaborative research effort dedicated to rewriting New England’s history to reckon with realities, such as the fact that, as they note, “over 1,740 documented transatlantic slaving voyages were made on vessels constructed and registered in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut or having departed from their seaports.”

“This type of research can take time,” said Gilmore of research like Tanzer’s, which focuses on Quash Winchell of Topsham. “But there is much to uncover and James and other researchers are part of an important effort to make sure the stories of our county’s Black history are discovered and shared.”

Researchers still face many challenges.

“It is not always easy to identify black folks from the record,” said Greene in a similar lecture – Black History of Maine – delivered on Jan. 28 at the Rockland Public Library.

Still, Greene said, the history is there.

“Did you know the first Black man in Maine we now know by name was here in 1608? That’s 12 years before the pilgrims arrived in Plymouth Rock. And two-and-a-half centuries before Rockland became a city,” said Greene.

That man was Mathieu da Costa, a sought-after interpreter of French, Dutch, English, Portuguese, Micmac, and pigeon Basque.

So began Greene’s presentation of profiles or portraits, a slideshow projection of names and images of Black people in Maine from the 1600s to 2022. The photographs and names were like an act of making visible again.

“Throughout Maine’s history there have been – and still are – Black folks who are quite visible, even if you don’t notice them,” said Greene. “Perhaps we Mainers just weren’t paying attention.”

He presented the list as a series of testimonies, not an exhaustive archive. Rather, the people mentioned gestured towards other historic absences and invisibilities, as audience-members’ questions showed at the end.

Through the invisibility, there is another kind of presence, a way to cut through, Greene’s work suggested.

And between 1820 and 1870, Greene noted, Black residents were documented in 274 towns in Maine, including a family of 10 in Bristol, who were listed as slaves on the 1820 census and free on the 1830 census.

Greene mentioned these stories and names not as footnotes but as traces, impressions, offerings. He also tied them to the present, not only noting present day Black Mainers, but also the lineage present in places like Portland’s Abyssinian Meeting House, considered a critical historic structure constructed by and for Black Mainers in the early 1800s.

The church was built “like a ship upside down,” said Greene, connecting its architecture to the long history of Black people working in coastal Maine’s shipbuilding industry.

Greene spoke to the topic of slavery, noting plainly that “there have been slaves throughout the state of Maine.” In his lecture, he referred frequently to the 2006 publication “Maine’s Visible Black History,” by Gerald Talbot and Harriet Price, the first book of its kind to address Black history in Maine.

Greene also devoted time to the historic Black community of Peterborough or Peterboro in Warren.

All that remains, as far as researchers know, is a cemetery.

The Peterborough cemetery is not marked on Google Maps. General directions can be found on the Warren town website.

Off Bunker Hill Road in Warren, a white sign marks the short trail into the cemetery. Snow-covered, the trail bears small footprints of animals.

The cemetery is wedged between two homes with a barrier of woods around its perimeter – and a chain-link fence. An American flag waves above the headstones, engraved with the names of the Peters family and other Black residents who lived in the area.

At another cemetery, this one in Wiscasset, Tanzer and his partner came across a tiny headstone facing Route 27. It bore the name Pendy Gustus, said Tanzer, spelling out the name from memory.

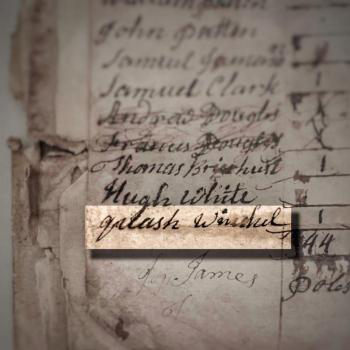

Curious about the name, Tanzer went to Lincoln County Probate Court and other records to learn more. He found Pendy Gustus in the 1850 census, but she was a dead-end. Or rather, a pathway somewhere else: To Quash Winchell.

“I thought I would just flip through the index to the very end, looking at names. And when I got to the Ws, I saw the name Quash Winchell,” said Tanzer, who had recently read a book called “Black Yankees” about slavery in New England that noted that African day-names were fairly common among enslaved Black people in New England at the time.

Tanzer started to wonder about Quash, looking for his name elsewhere. “And that was how I found this will,” he said.

“He talks about being enslaved in his will. I’ve never seen anything like that in Maine before… So it’s a remarkable document. And then once I found his will, I was like, this is amazing. Like, this is stunning. Somebody must have written something about it,” said Tanzer. “At one point, I found that his will had actually been transcribed. So somebody had transcribed it and published it in a book of Lincoln County wills. But nobody had researched anything about him.”

By 1781, Quash was free and living on his own in Topsham, which at the time was a part of Lincoln County. Quash was a farmer who owned property, tended animals, and sold his labor.

His will, Tanzer notes, provides a comprehensive list of all of Quash’s possessions at the time of his death, providing remarkable insight into the man’s daily routines, economic standing, tastes, preferences, and skills.

Tanzer’s upcoming talk focuses on Quash’s life and legacy in the Topsham area.

The entry of Quash Winchell in Lincoln County records. (Courtesy photo)

Though Tanzer is still asking questions as to how Quash Winchell ended up in Maine, he learned what he now knows about Quash’s life from local public records.

Sometimes, it’s just one word, said Tanzer, like a seed. It leads somewhere else.

But it also leaves a host of open-ended questions. Tanzer is still researching the life of Quash and sharing his research through lectures and through the Atlantic Black Box Project.

As a researcher who left academia, Tanzer noted that he makes a point of sharing any and all of his sources. In this work, he said, it is critical to be open and to collaborate, mentioning the support of the Pejepscot History Center, among others.

Tanzer spoke about the dangers of a “curated history” that erases or minimizes slavery in New England.

But Tanzer also acknowledges the absences in archival materials, school curricula, and published books that make an anti-racist history of Maine that includes Black history more difficult to tell. In response, Tanzer leans into the absences.

“I like to say ‘perhaps’ a lot to lean into that generosity,” said Tanzer. “I was trained as a social historian, and I feel like if we’re not more, ‘perhaps-y’ then we will never end up telling any kind of story at all.”

The perhaps-es are sparked by traces in the archives like the name Quash Winchell.

Gilmore, Greene, and Tanzer all noted that, despite both willful cover up and negligence or lack of research, such traces are still everywhere, including present-day Lincoln County.

For example, on Louds Island in Muscongus Bay. The island has a long history of indigenous and then settler-colonial inhabitants; the last year-round residents left in the mid-20th century, after the school closed. The island is still unincorporated, now home to summer residences and the Elizabeth Noyce Preserve.

And a church, known as Loudville Church. A National Register of Historic Places registration form submitted for the church in 1995 includes two descriptive paragraphs written by then Columbia University Professor of Architecture Emeritus Adolf Placzek.

Placzek wrote: “The Loudville Church, an attractive structure built in 1913, stands today as a reminder of a long period in Maine history when offshore islands played an important role in the State’s economy and were able to sustain year-round populations. In addition, the church building recalls a deplorable incident of long ago: The eviction in 1912 of the mixed-race inhabitants from Malaga Island where they had lived as unchallenged squatters since the mid 1800s. In January 1913, the State purchased Malaga Island and tore down all the buildings except for the four-year-old schoolhouse which was given to the Maine Seacoast Missionary Society. Dismantled and shipped to Louds Island, the schoolhouse provided much of the lumber used to build the Loudville Church.”

As Greene said in his talk at the Rockland Library, “I don’t want you to leave thinking this state has been the perfect host.”

Greene noted historian Patricia Q. Wall’s book, “Lives of Consequence,” which compiles and chronicles the lives of many enslaved Black people in the Kittery area. And census data, and town records, and tax records, and other smaller fragments of history that help to understand the prevalence of slavery and anti-Black racism in Maine’s history.

A recent exhibit at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath, “Cotton Town: Maine’s Economic Connections to Slavery,” was created in collaboration with Bowdoin College’s Africana Studies Department and is on display until May 8.

Tanzer said the most troubling response he has received when presenting his research is when people counter that there was no slavery in Maine.

“It’s shocking to me, when I talk about my project to other people, how many people counter that with, ‘but we didn’t have slaves, and we didn’t have slaves in New England.’ And I think that’s really what has played on my heart … there is such a rich history here of enslaved and free people of color. And that knowledge has been forgotten, covered up, ignored, maligned indifference,” said Tanzer.

“That’s the only reaction I’ve gotten, because most people have been like psyched about (the research). But there’s people who are just confused, I guess. By the presence of enslaved people in Maine. Maybe that’s what bothers me the most,” he added.

As his work – and that of Bob Greene, George Talbot, Patricia Wall and so many other researchers – attests, Tanzer explained, this statement is disturbingly inaccurate and contributes to further erasure, further invisibility.

“As we do this work to uncover hidden histories and share them with the public, we will inevitably be confronting instances of prejudice, racism, mistreatment, ties to the slave trade, and enslavement,” said Gilmore of the LCHA. “It’s important that we do the work to acknowledge that these uncomfortable elements are part of our local history. As we begin to more fully understand the history of our region, we can better contextualize the present.”

Gilmore promised this month’s lecture series is part of an ongoing effort, not an end goal.

“Though we offered this programming in celebration of Black History Month, Black history is something that we need to be aware of every month,” she said. “LCHA will certainly be offering more programming associated with this work in the future.”

Tanzer will present his lecture “Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way: Uncovering the Life of Quash, a Black Man in Eighteenth-Century Lincoln County,” at 6 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 24, through the Lincoln County Historical Association. More information is available on the LCHA website under “Events.”