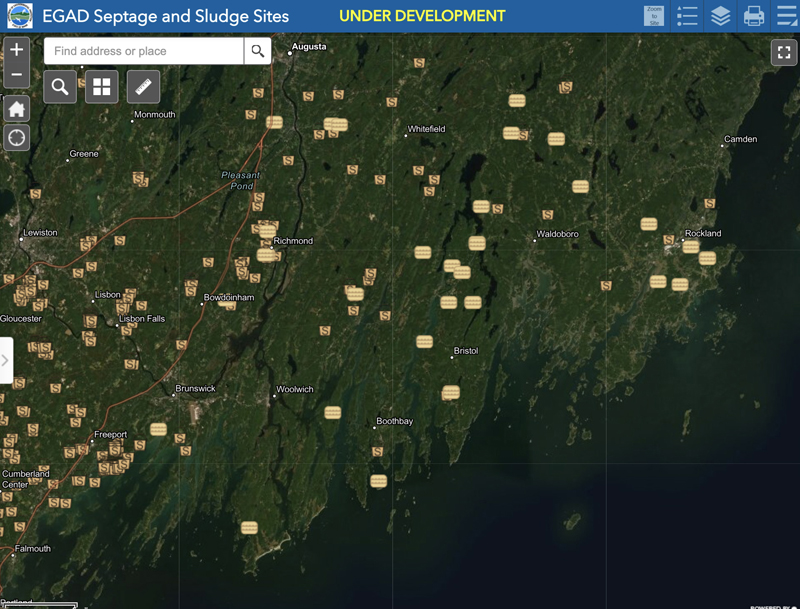

Lincoln County on the Maine Department of Environmental Protection’s Septage and Sludge Sites map, which is under development. Sites mark where sludge application was licensed and don’t necessarily show whether or not it was applied. Any errors or omissions on the map should be reported via email to pfas.dep@maine.gov. (Screenshot)

“It wasn’t something that was on our radar at all,” said Jessie Dowling, a cheesemaker with 15 years experience and owner of Fuzzy Udder Creamery in Whitefield.

That “it” is PFAs, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

PFAs are a group of chemicals that have been used in industrial and home products since the 1940s, according to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Thousands of versions of these chemicals have been used by manufacturers for products from non-stick cookware to water-resistant clothing. But the chemicals break down slowly and have been known to build up within ecosystems and individual’s bodies.

Human health risks from build-up may include decreased fertility, increased risk of cancer, reduced immune system function, hormone interference, child development effects, increased cholesterol and risk of obesity, and high blood pressure in pregnant people.

In October 2021, after a law authorizing and funding investigation into PFAs went into effect, the Maine DEP published a list of 34 priority sites where more than 10,000 cubic yards of sludge, septic tank sewage, or industrial waste were used as fertilizer with licensing from the department.

While none of those sites fall within Lincoln County, farmers in the area are stressed and concerned for their peers – and, in many cases, still waiting on their own data.

“And having this fear that like, it could be the tip of the iceberg where we really just don’t know until we have more testing done,” said Dowling.

A press conference for impacted farmers was held on Feb. 23 in support of LD 1911, the bill that “could close loopholes that currently exist that allow farms and gardens to continue to be contaminated by toxic PFAS chemicals,” according to environmental justice nonprofit Defend Our Health. Senator Chloe Maxmin, D-Nobleboro, is a co-sponsor of the bill.

On Feb. 24, the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association and the Maine Farmland Trust announced a new PFAs Emergency Relief Fund. The effort is intended to ease financial, emotional, and environmental stress for farmers. Both organizations also provide informational resources and updates.

Misinformation is a major concern and part of the reasoning behind the recent press conference. And even for experienced farmers like Dowling, there’s still a lot to learn.

“We actually routinely test our products for pathogens,” she said. “That’s what our training as cheesemakers is in, is testing for food safety. But the PFAs has never been…in any food safety training courses. It’s never been in any of the cheesemaking courses I’ve taken over the last 15 years. So it’s really not been something that we as farmers are prepared to deal with. It’s all kind of new coming at us.”

The new Emergency Relief Fund may help farmers test their land and water – still, waiting for results has put farmers in limbo.

“It’s a terrible situation,” said Barbara Boardman, owner of White Duck Farm in Waldoboro. For Boardman – like others in the County – questions and frustrations remain.

Among Boardman’s questions: “When did the state first know this was a problem?”

Some answers are available through Maine Farmland Trust, MOFGA’s “PFAS Maine Farmer Information and Support” web page, Defend Our Health, University of Maine Agriculture Cooperative Extension website, and on state departmental websites.

Dowling has been relying on MOFGA for information and updates – as have many other organic farmers in the state, who also expressed concern that the current contamination situation will be mis-attributed to organic farming practices.

Farmers from Dresden to Waldoboro are not just worried about their own land and reputation, but also their friends, peers, and suppliers, who are all part of the ecological and economic matrix of Maine agriculture. They expressed support and sympathy for those who have been more severely impacted.

“We all know where we grow, but these are questions we’ve never thought to ask our suppliers,” said Dowling, who typically buys in milk from Misty Brook Farm in Albion and Organic Jersey Cow’s milk from Grace Pond Farm in Thomaston, in addition to the milk from her own animals.

Misty Brook Farm’s milk tested high for PFAs contamination in early February, leading the farmers to pull their products from the market. They tracked the contamination to their hay and said this was the first time they had purchased from those fields.

“It breaks our hearts to think we sold any contaminated food, but we are so glad we caught it quickly,” they wrote in a Feb. 19 statement on social media. Misty Brook Farms farmer Brendan Holmes also spoke at the recent press conference.

Boardman had just reached out to the farm that supplies her hay to see if they had any new information about their fields.

In Wiscasset, the Morris Farm Trust is actively seeking more information on the sludge that was applied to 5 acres out of its 50-acre property in the early 1990s.

President David Landmann echoed concerns for all farmers who sell through Morris Farm Trust store, too. A statement with more information can be found on their website at morrisfarm.org.

Other Lincoln County farmers are still working to test their water and land.

Yet the contamination – often linked to sludge from wastewater treatment facilities, landfills, and industrial sites like paper mills – is not limited to farms.

Sites where sludge-spreading was licensed are mapped on the Maine Sludge and Septage Mapper, a project created by the DEP. On the map, over 20 sites are listed in Lincoln County.

On another map, the Maine PFAs Mapper, which documents sites where PFAs testing has occurred, only four sites appear within the county.

“The recordkeeping for the licenses may not have been very exact, and locations on the map may suggest a general vicinity, not exact fields,” reads an interpretation on the MOFGA PFAs resource page. “Where there is contamination, PFAS concentrations are proving to be highly variable within fields, and neighboring fields can have very different amounts. ‘Stacking’ or ‘stockpiling’ sites where bio-solids were piled up before being spread out tend to be where levels are highest. Groundwater contamination may be different however, as subsurface water doesn’t necessarily respect field boundaries.”

Both maps are under development and urge input via email at pfas.dep@maine.gov. And with research and testing ongoing, they are likely to change.

Dowling said she should get her test results back by mid to late March – her and many other farmers at a similar stage. Until then, work goes on – in the fields and in the State House.