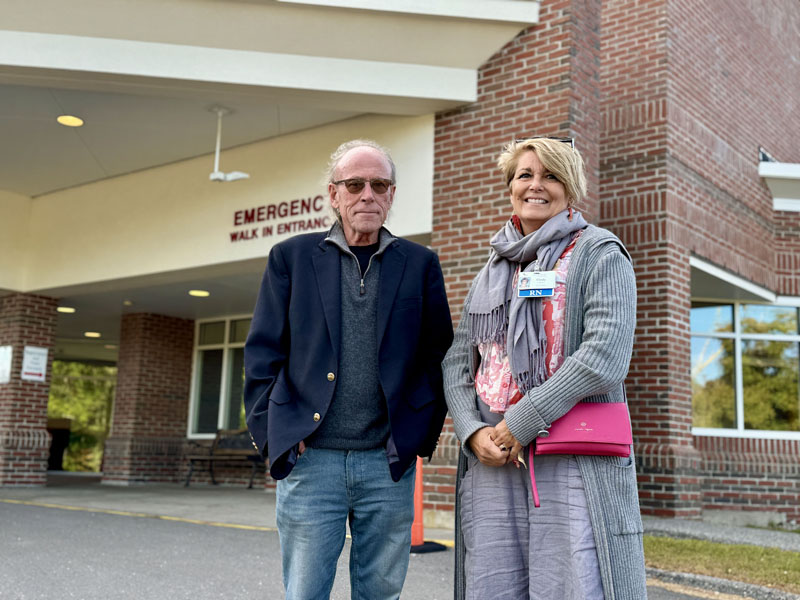

Addiction resource advocate Tim Cheney and MaineHealth Lincoln Hospital President Cindy Wade stand outside of the emergency department at the Miles Campus in Damariscotta on Sept. 24. Cheney and Wade worked together to install New Englands first free Narcan vending machine at a health care facility. (Johnathan Riley photo)

An opioid-overdose antidote, naloxone, is now available free of charge from a vending machine in the entrance to the emergency department of MaineHealth Lincoln Hospital’s Miles Campus in Damariscotta.

Hospital staff finished installing and stocking the vending machine with Narcan, a brand name for naloxone, on Friday, Nov. 15, according to MaineHealth Lincoln Hospital President Cindy Wade.

“(Narcan) reverses effect of the opioids and basically brings people back to life, if they’ve overdosed to the point where they’re unconscious, (and) unresponsive,” Wade said. “This is a health care crisis in our country and we’re trying to find ways to help support people.”

According to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were approximately 10,000 drug overdoses in Maine in 2023.

The idea to facilitate a vending machine dispensing naloxone at the hospital was pitched almost a year ago to Wade by Walpole resident Tim Cheney. As an addiction resource advocate and founder of the substance use disorder treatment program, Enso Recovery, Cheney has a long history of advocacy, which informed his donation of the vending machine to the hospital.

“I came to Cindy and we started talking about it and she was right on board immediately, which we were thrilled,” he said.

The installation of the vending machine is the first of its kind in New England at a health care facility, according to Cheney.

Wade said she took the idea to medical staff committees at the hospital, which received approval.

“I wanted to make sure the medical staff supported it, I didn’t think they wouldn’t, I just wanted to make sure that we were doing all the proper channels,” she said.

Beyond medical staff committees, the idea was approved by the hospital’s executive board, MaineHealth’s legal department, and Dr. Kate Cavanaugh, the hospital’s medical director for substance use disorder, before it was installed.

While the idea has the approval of the hospital’s medical teams, Wade said there is still “a little apprehension” from some members on the night shift, who were concerned about the possibility of drawing more people to the emergency department at night.

Cheney said it’s likely a high percentage of those using the vending machine will be friends and family of people with opiate addictions.

“I’ve worked a lot over the years to try and change the perception of addiction from a criminal, secondary deviant subculture, behavior criminal moral issues, into a health care issue,” Cheney said. “The best way to do that is to incorporate it into the medical system to normalize it. People are going to see this as they walk in there and whether they acknowledge it consciously or subconsciously, or whatever, eventually they’re going to start associating that with medical (care).”

Wade said the hospital personal will stock and monitor how much the vending machine is being used to adjust the amount of Narcan available to meet the needs of the community.

In order for individuals to receive Narcarn from the machine, coupons are available in a brochure holder beside the vending machine located in the breezeway entrance to the emergency department. The coupons, roughly the size of a dollar bill, are inserted in the machine and the Narcan is dispended at no cost.

Wade said in the MaineHealth’s physician practices, Narcan is provided to those in need of the product, whether it is for themselves or someone who needs it.

“This is a sort of self-serve, it’s a whole another way for accessing it,” Wade said. “It eliminates the shame; this is something we want available to people if they need it.”

Cheney and Wade said vending machine is available to all who need it or who know someone who does, 24/7.

In the future, other items in demand of emergency department patients, such as feminine hygiene products, may be stocked. The idea, suggested by hospital staff, would provide another reason to approach the vending machine, further reducing any stigma, Wade said.