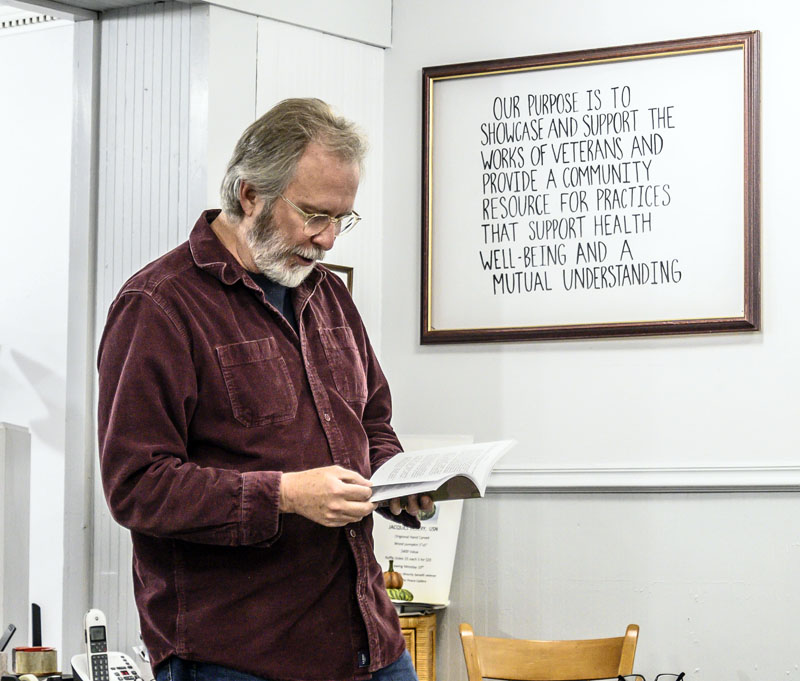

Ron Capps reviews information from his book Writing War during a veterans writing workshop at The Peace Gallery in Damariscotta on Oct. 18. Capps, who served as both a soldier and a foreign service officer in countries like Kosovo, Rwanda, and Afghanistan, founded the Veterans Writing Project, a nonprofit organization that supports writing workshops around the country. (Bisi Cameron Yee, LCN)

A local workshop for veterans is helping its members harness their talent to write.

The workshop, which meets in the Peace Gallery in downtown Damariscotta, is a branch of the larger Veterans Writing Project, an organization founded by current Edgecomb resident Ron Capps.

According to Capps, the nonprofit donor-funded Veterans Writing Project has been providing no cost writing seminars and workshops to both veterans and family members in 25 states since 2011. The partnership with The Peace Gallery, founded by Vietnam veteran Bernie DeLisle and managed by him and his daughter, Olivia, started in March 2022.

“I think Bernie is creating this really interesting environment, creating a community where art is by veterans and family members,” Capps said. “We want to take the art and make it visible and available to the greater community. It’s a way of bridging the divide between veterans and those who have not served.”

On Tuesday, Oct. 18 a group of writers met at The Peace Gallery in Damariscotta to discuss their works in progress.

Jeff Stewart served aboard the USS Kitty Hawk and the USS Carl Vinson out of San Diego in the early 1980s. He is working on the first draft of a novel set in the aftermath of World War I.

During the meeting Stewart read a section from chapter three that describes an episode of post-traumatic stress disorder in vivid detail.

When the episode is over and his character heads home, the echo of war remains: “… the moon gave everything a silvery glow — the same silvery glow he’d looked through toward the German line … What is it about the moon that steals color?”

The group called out a few small inconsistencies and discussed some of the language, how metaphors clarify meaning.

Stewart took the opportunity to ask the group if PTSD comes on suddenly, “Boom!” or more slowly and what things can trigger it.

Jeff Stewart gives feedback during a veterans’ writing workshop at the Peace Gallery In Damariscotta on Oct. 18. Stewart, who served in the navy, is writing a novel set in the Jazz Age just after World War II. (Bisi Cameron Yee photo)

Writer and Marine Corps veteran William Palmer said it’s sometimes brought on by color or sound, perhaps the backfire of a truck. For those who have experienced incoming artillery and resulting PTSD, “when we pick ourselves up off the ground after the episode, it’s embarrassing,” he said.

Capps was moved by a section in the chapter in which the handle of a shovel digging a grave is transformed into the butt of a rifle, calling it perfect.

“One of the best descriptions of intrusive imaging I’ve heard,” he said.

Palmer is collecting what he calls more humorous military water-cooler stories to share with his 15-year-old grandson. He read aloud to the group from his memories of a mission in South Korea.

“One of the reasons I enlisted in the Marines was I was hungry,” Palmer said. “When I went to the recruiter I was an unemployed college student. He assured me ‘you’ll always have chow.’”

As Palmer continued, it became clear that there were exceptions to that rule. After a two-day patrol turned to three and rations ran out for the 160-man company, “we sat tight on the beach that night … we were down to several packages of instant coffee and a can of peanut butter.”

Palmer took detailed notes as his offering was critiqued. The group found the story strong but in need of more details – the sounds, the smells, how the landscape looked. Capp suggested contextualizing some of the military jargon.

“It’s a fine line to walk between using specific language and losing your audience,” Capp said.

One suggestion was that Palmer describe the chow when the troop was finally fed, how it tasted. Palmer’s question whether anyone really wanted to know how military chow tasted was met with the laughter of shared experience.

Stewart, now a pastry chef, lives in Southport. He has a master’s degree in creative writing, has taught writing, and has participated in a number of writing workshops in the past.

Stewart didn’t initially think much of his writing was informed by his time in the military, but said he’s tapped into it more since joining the veterans group.

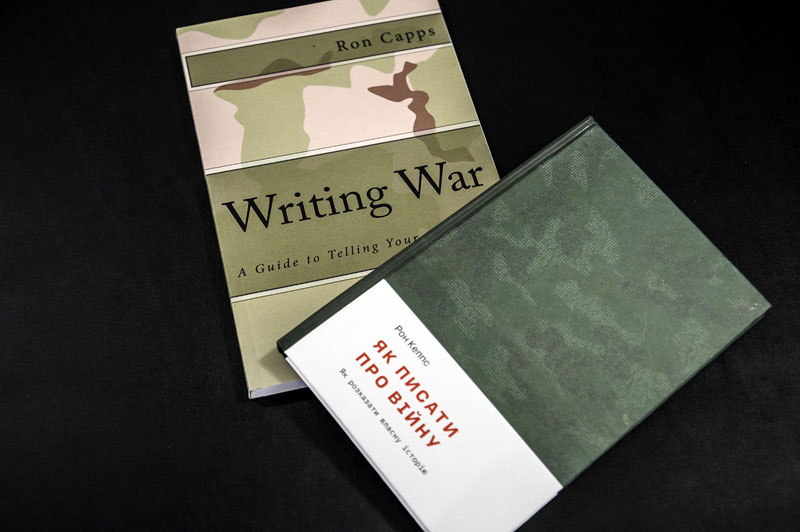

Copies of Ron Capps book, “Writing War, published in both English and Ukrainian are available for the veterans writing workshop at The Peace Gallery in Damariscotta on Oct. 18. The book is the basis for the curriculum presented during workshops sponsored by the Veterans Writing Project. (Bisi Cameron Yee, LCN)

“We understand each other. We have a shared sense of humor, we get the same jokes. We know the sacrifice each (of us) has made,” he said.

Stewart contrasted the group to some others where the criticism can be harsh.

“It’s not kid gloves and hugs,” he said, but it is “a wonderfully comfortable group to be a part of.” He credits the relationships he’s formed there with improving his writing and keeping him motivated.

Stewart brings his work to the group because “there are people there who have had experiences and can check the authenticity” of how he writes. While he has experience with military life, he was never in combat and never experienced PTSD.

Some of the writers in the group enjoy putting their work out there and seeing what people think, Stewart said. For others it can provide a catharsis – “a way of expunging the demons.”

“Not everyone writes to publish … Some just write to get it out,” he said. “Write it, rip it up, throw it in the wood stove. It’s a wonderful way to perform therapy … to get things out of the head and out of the heart that may be impeding progress.”

Palmer aspired to be a writer when he was in high school, but decided chemical engineering provided more career options. He joined the Marines after his first year of college and continued his education while in the Corps, receiving college credits in math, physics, chemistry, engineering, and a degree in history.

While he was always good at grammar and was often pegged to write up reports for his superior officers, Palmer said he never really wrote until he joined the group at The Peace Gallery.

Palmer’s service started in Vietnam where he proved himself a leader during reconnaissance missions.

“It was something I was good at,” he said. “I’m a sneaky son-of-a-gun.”

A whiteboard features diagrams of story structures to be reviewed during the veterans writing group at The Peace Gallery in Damariscotta on Oct. 18. The structures discussed include such classics as the parabolic boy meets girl and the stairway followed by a fall from grace followed by redemption, which reflects stories dating back to the Bible. (Bisi Cameron Yee, LCN)

The troops he served with often told him he should write down their stories. Like the time he was sent out with a team to do a bomb damage assessment after a B-52 air strike. After he landed he radioed a thank-you to command for the artillery support provided. They responded that if he was seeing fire it was because he was surrounded. Palmer and his patrol wound up tracking an enemy patrol to the perimeter and made it out without shots fired.

Palmer said he values the camaraderie, the encouragement, and the constructive criticism in the group. In addition to the story collection, he has outlined a series of detective novels featuring a Maine soldier who returns from war and settles in Portland as a private investigator. He’s completed much of the historical research and looks forward to putting the lessons he’s learned on story structure and character development from Capps’ writing curriculum to the test.

Fred Nehring served aboard the USS Philadelphia out of Groton, Conn. in the 1970s. He writes for his own amusement and joined the group to sharpen up his writing skills, he said in an email.

Nehring said the military experience changes a person in a very profound way.

“Most people enter the military, as I did, out of high school,” Nehring wrote. “The training and discipline is completely alien to the prior civilian experience.”

He said service members have been trained to function under extreme stress, to work together in concert and watch each other’s backs.

“You are consumed by your duties with very little personal time.”

He described leaving the military as leaving a brotherhood and being alone in the civilian world.

The Peace Gallery in Damariscotta hosts a monthly veterans writing workshop for veterans and family members who want to explore how writing can help them process their experiences either for themselves or for possible publication. (Bisi Cameron Yee photo, LCN file)

“It’s good to be among fellow veterans with whom I can share experiences … who understand the nature of military experience,” he said about the group.

Capps served 25 years in the Army and Army Reserve, including a stint in Afghanistan. He has written essays, plays, songs, a memoir and a book titled “Writing War: A Guide to Telling Your Own Story,” which serves as the curriculum for Veterans Writing Project workshops.

Capps said there are a number of reasons veterans don’t often share their memories of military service. Some aren’t comfortable talking with people who have not shared their experience. And sometimes the words don’t come.

According to Capps, writing can be the tool to access those words. It creates a filter between a veteran and a memory and it allows them to hold the memory long enough to shape it.

“Every veteran has a story,” Capps said. He sees his mission as helping provide the skills and the confidence to write it.

The veterans writing workshop meets one Tuesday evening a month. To receive the current schedule, email roncapps@gmail.com.

For more information about the Veterans Writing Project go to veteranswriting.org.

For more information about The Peace Gallery, go to thepeacegallery.com.