At 88, Howard Cederlund is working to ensure the experience of Pacific Theater veterans is preserved for future generations. (Photo courtesy Anne Cederlund)

Since the end of World War II, Howard Cederlund has traversed the North American continent and traveled internationally, oftentimes reuniting with his former shipmates aboard the USS Menard and their surviving family members. The Pacific region, however, is an area of the world he has no intention of returning to, he said.

At the young age of 17 and 18, Cederlund served as a gunner’s mate third class aboard the USS Menard, an amphibious personnel attack transport vessel responsible for offloading “beach parties,” or small battalions leading the charge in the island invasions of World War II’s Pacific Theater.

In his two years in the U.S. Navy, Cederlund survived the Battle of Okinawa, the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War, experienced firsthand the United States’ two secret weapons of World War II, and dodged mines and navigated through typhoons to transport troops from the Pacific Theater home at the war’s end.

The true experience of Pacific Theater veterans is not an easy one to share, Cederlund said. Many have refused to talk about what they saw and felt as they battled Japanese forces in the Pacific region. “There was a lot of horror,” Cederlund said. “Horrible things went on. How do you talk about that with people?”

At 88, Cederlund’s goal is to be the oldest surviving veteran of the Pacific war and is committed to canonizing his experience aboard the USS Menard. Cederlund self-published “This Is The Way It Was!” a chronicle of his life in the Pacific War, in 2004, which he has made available as a free download online.

The granddaughter of one of Cederlund’s shipmates contacted him to ask about what her grandfather had been through in World War II, which his shipmate never shared with his family. It inspired Cederlund to write his book.

For the sake of his children and grandchildren, the graphic details and gruesome descriptions of what he experienced were left out, he said.

Cederlund enlisted in the Navy in 1944 at 17, a choice he made to protect his family. “I couldn’t stand the thought of my parents becoming slaves to the Germans or the Japanese,” Cederlund said. “Our country was in rough shape. We were really trying to save America.”

Decades after the war’s end, Cederlund would read “I Was a Kamikaze” by Ryuji Nagatsuka, a rare insider account of the mentality of Japan’s kamikaze pilots. “He went into the service for the same reasons as me,” Cederlund said of the author. “He was no different than I was. Old men start the wars and the young men fight them.”

In April 1945, however, Cederlund was stationed off the shore of Okinawa manning the USS Menard’s anti-aircraft guns and shooting down Japan’s kamikaze planes and dive bombers before they killed him and his crew. On April 6, 1945, alone, over 700 Japanese planes attacked U.S. naval forces – 350 of which were kamikazes.

Cederlund’s friend and shipmate, Eugene White, was mortally wounded in the attack. The crew took up a collection for his widow, Ruth White, who, in return, requested extra sugar from the rationing board in the U.S. to be able to bake and send cookies to them. Ruth White sent a handwritten note to one of the USS Menard officers thanking him and the crew for their thoughtfulness.

For nearly 55 years, Cederlund attempted to track down Ruth and Eugene White’s children. He was finally able to find them, six months after Ruth White had passed away. At a reunion, Cederlund was able to present Eugene White’s daughter, Nancy, with Ruth White’s handwritten note.

“It was incredibly emotional,” Cederlund said. “It may be one of the last stories from WWII like that.”

Just in the past few years, Cederlund met Round Pond resident George Hanna through happenstance and discovered their shared history. On April 2, a kamikaze plane shot by the USS Menard crashed into Hanna’s ship, the USS Achernar, killing five of its crew.

The two never knew each other before their chance encounter, but on the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, the two celebrated together. Hanna has since passed away.

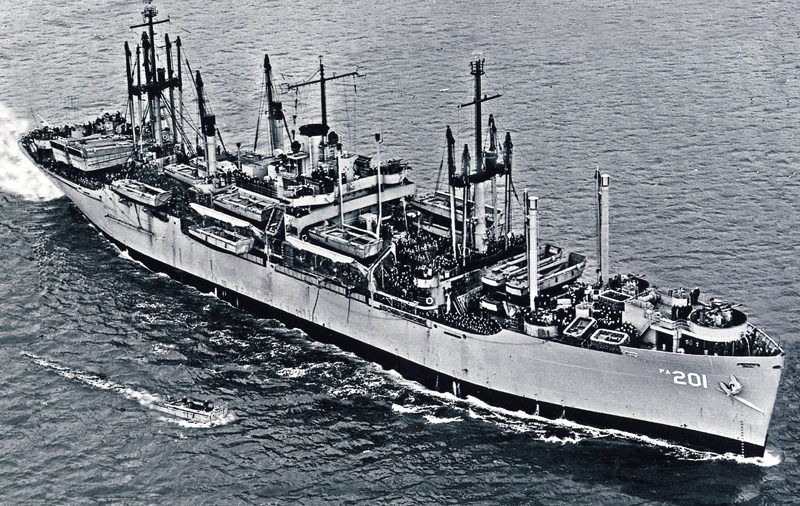

The USS Menard carried U.S. troops home as part of “Operation Magic Carpet” in 1945 and 1946. (Photo courtesy Howard Cederlund)

Aboard the USS Menard, Cederlund actively worked with one of the United States’ secret weapons, which helped the Allied forces win the war. Proximity fuses were installed in some of the anti-aircraft weapons aboard the ship, which enabled shells to explode when their targets were within 70 feet.

“We suddenly became great gunners and became very good at shooting down planes,” Cederlund said. Shells armed with proximity fuses were among the first smart weapons introduced by the military.

Cederlund and the crew of the USS Menard would be among the first from the U.S. to encounter the other secret weapon of World War II – the atomic bomb. The USS Menard was slated to be the lead ship in the invasion of mainland Japan to be launched from Okinawa. After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the invasion was no longer necessary.

The USS Menard, however, was the first ship to deliver troops to the bomb site at Nagasaki. “We never heard of the atomic bomb,” Cederlund said. “We were walking around, we had no idea about the radiation. All we knew was that there was some super bomb, some secret weapon.”

Officials set the death toll at Nagasaki between 60,000 to 70,000 people, according to the Atomic Bomb Museum. The crew and troops aboard the USS Menard were among the first to witness the devastation. Many U.S. troops experienced cancer as a result of radiation exposure at Nagasaki, Cederlund said.

What he saw and experienced at Nagasaki he will carry with him for the rest of his life, Cederlund said. However, Cederlund said he felt so strongly that dropping the atomic bombs was the right decision, he traveled to Harry Truman’s grave to thank Truman for making it.

“If you ask anyone who served in the Pacific if dropping the bombs was the right decision, the answer you’ll get from them is a resounding yes,” Cederlund said. On mainland Japan, Allied forces discovered more than 10,000 kamikaze planes ready to attack. “They were never going to give up,” Cederlund said.

In August 1945, when the western world celebrated the end of World War II, the crew aboard the USS Menard was still on duty. As one of its last missions for World War II, codenamed “Operation Magic Carpet,” the USS Menard transported troops from the Pacific Theater home to the U.S.

Cederlund never had the opportunity to participate in the celebrations at the end of the war. A presentation of a certificate at Wings Over Wiscasset in 2014 and the standing ovation he was given after playing a tune on his harmonica, which he used to play on the USS Menard, was a rare moment of recognition for him.

“It was a great honor to be recognized like that and to be able to share our stories,” Cederlund said.

The USS Menard served in the Korean War before it was decommissioned, sold to the Gillette Company, and turned into razor blades, Cederlund said. Its history, however, lives on. Howard Cederlund is making sure of it.

“This Is The Way It Was!” is available for download at www.ussmenard.com/book.html.