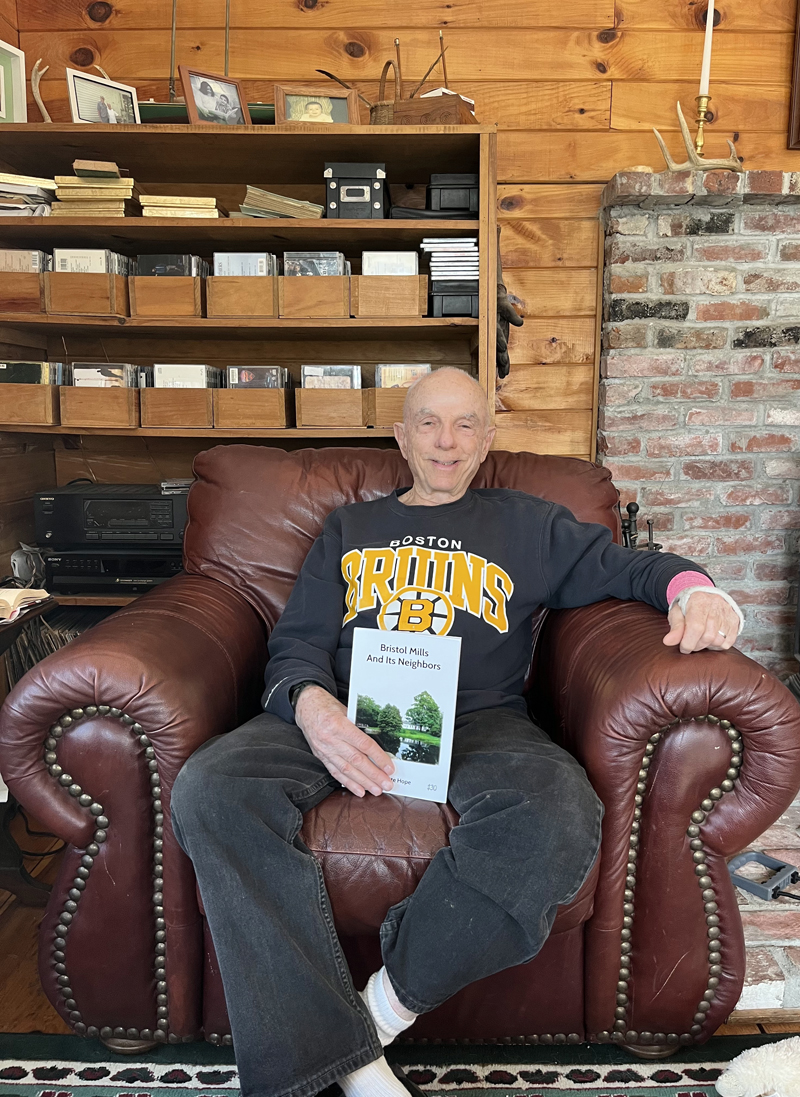

Pete Hope with his latest book, “Bristol Mills and its Neighbors” in his Pemaquid home. (Anna M. Drzewiecki photo)

Pete Hope pointed out the window at the clam flats behind his home, nearly glistening. His dog Harrington lounged in the sun. Spring birds hummed from outside.

“Clamming was my first love,” said Hope, who grew up on a farm across the road from his current home in Pemaquid. Then perhaps history was his second? Or maybe this land? Or teaching? Or writing?

“I came back here about 20-odd years ago. And I wasn’t here too long before I started interviewing older people, all of whom except one have since died,” said Hope. “You know, this is what I told my students: This is very important stuff. Because if you don’t record your grandfather’s story, it’s going to die with him.”

“Anytime I could fit it into my curriculum, I did,” Hope said of oral history. He paused, and then asked questions in response, as if emulating his oral history practice for his own oral history record.

Thick beams line the insides of Hope’s home, which he built from timber salvaged from the nearby farm.

“My dad was a poultry farmer. I like to say the only poultry farmer in the world with a Yale diploma and a philosophy major. I’ve always thought that was pretty neat,” said Hope, adding, “And I’m also quite sure that I was the only Bowdoin graduate ever to come up a professional clam digger!”

At the liberal arts college in Brunswick, Hope studied European and Russian history. A passion he followed to graduate school, where he earned a master’s in history at Boston University.

“I did not become a teacher for any idealistic reason,” said Hope, whose mother was also a teacher. “I went to grad school in history, and halfway through the year, it dawned on me, what the hell am I going to do?”

His mother made the profession seem noble, he said, plus, the schedule could work seamlessly.

“If I taught school, I could clam all those vacations, and that would be great,” said Hope.

And he did, teaching at Camden-Rockport High School, “which is no more,” in his words, and clamming off Swan’s Island, Vinalhaven, and elsewhere.

To clam, he traveled Maine through its topography. “I dug everywhere from way Downeast to Portland,” said Hope. He also participated in the clam depuration program, while it was in action.

“This is just one cove of many,” he said, again gesturing out to the cove behind his Pemaquid home.

To teach, he traveled Maine through time, organizing oral history projects with students in classes and for the high school’s Folklore Magazine.

What might be one story of many – or one wharf of many – to others is a story – or a wharf – apart to him.

Since returning to the peninsula, Hope has been actively exploring histories of the surrounding towns, islands, fishing and lobstering. Of industry and family life, stories of the domestic and the municipal.

It started, here, with the wharves.

“At some point … someone said to me, ‘You ought to find a story of all these wharfs in New Harbor. Before it’s too late.’ So I did,” Hope said. “I got a guy I had gone to school with years ago, who was manager of what is now Shaw’s Wharf to go around with me. And he knew the history of every one of them.”

They drove from wharf to wharf, recalling and recounting.

“Some of them had been in the same family for generations … maybe one or two of the commercial ones had become private wharfs,” said Hope. He mentioned the steamship wharf, where steamboats would come into New Harbor “on a regular basis.”

“There were several different steamship lines up and down the coast,” explained Hope. “It’s a lot more dependable than schooners as far as establishing a set schedule, which you could rely on. Not as pretty as schooners though.”

The wharf project sparked Hope’s idea to write a longer history of New Harbor – a book that would become the first in a series of works on the towns of the Pemaquid Peninsula.

“Bristol’s made up of a lot of different communities, historically, not so much now,” he said. “I decided I would write a history of every community.”

His latest, published in early 2022, is “Bristol Mills and its Neighbors.”

“My wife and I particularly in this last one have done a lot of title searches. So as much as possible, I try to get primary sources,” the historian said.

He used deeds, letters, and diaries, too. For the other works, he relied on archives of a weekly newspaper called the Pemaquid Messenger, which ran during the late 19th century and had “just gossipy type of things, but some of them were pretty interesting and you got a good idea what was going on at that time period,” said Hope.

The Maine Register was a key source for his latest book. From its records, Hope gleaned a critical observation: In the mid-1800s, “Bristol Mills was humming.”

“I don’t know how many stores,” said Hope, emphasizing the sense that they were almost innumerable compared to current businesses. “A tannery, someone making shoes, someone sewing clothes. And most of all mills. It was a real mill town, and it was the hub of Bristol.”

“Bristol Mills and its Neighbors” is available for purchase at a few local stores, including Granite Hall in Round Pond, and through the author directly.

To buy the book – or any previous editions – one must almost encounter the history held within them. To buy his book on Pemaquid, one must go to the Seagull Shop, almost a stone’s throw from the lighthouse itself. The streets one must drive – or river one must ride on – to get to these stores are the same ones traversed by, haunted by, residents past, by steamship riders, farmers, millworkers, fishermen.

But then again, the books are now nearly history, too.

“Well, I sold them all,” Hope said. There are still copies of his “Bristol Mills and its Neighbors” available for purchase, and copies of the other books are housed at local libraries, not far from the archives and records he used to source the stories within.

An oyster shell grows in layers, adding on to what was there before. So too do Hope’s histories, almost like palimpsests, stories upon stories, the same location shape-shifting through time. He gave the example of what is now the Contented Sole restaurant, in New Harbor. It was once a clam factory, he said. Then it was Gilbert’s Lobster Pound. Now it is a restaurant, serving food as locally-sourced as Hope’s historical narratives.

“There were canneries in New Harbor, and I think Round Pond, where they canned lobster,” said Hope. “And of course back in those days, people went lobstering in dories or peapods and 100 traps … it was all manual. And 100 traps were a lot.”

“I learned about several drownings of fishermen,” said Hope, with a sense of refrained sadness. “No, more than several. I could probably almost write a book on that.”

In the geography of his research, Hope said he probably learned the most about Louds Island in Muscongus Bay, if only because it was the most unknown to him before.

“I probably learned more about that than any single place, like any other place that I researched,” said Hope. The community there “goes way back … Fishing, but you know, like everyone did back then, everyone had a cow and a garden. Little farms.”

“Now to be honest, I don’t know what I’m going to do next,” said Hope, gearing up for a bike ride with his dog. “I might – all those interviews I did – I might put them all together in a book.”

Another book, that is, to file under the name “Pete Hope.”