Herman Lovejoy stands outside of his home in Alna on Wednesday, July 7. Lovejoy has had several close brushes with death during his long career, beginning when he was hospitalized with polio at the age of 8. (Evan Houk photo)

During an hour-long conversation with Alna resident Herman Lovejoy on Wednesday, July 7, he cited at least six times when he found himself in a life-threatening situation, and there certainly seems to be more stories of that ilk that Lovejoy decided to keep closer to his vest.

“I think I’m using them up faster than I should be,” Lovejoy said when asked if he has nine lives.

The Benton native’s first brush with death came when he was 6 years old, diagnosed with polio, and admitted to a Shriners Hospitals for Children.

“If it wasn’t for the Shriners, I wouldn’t even be here talking to you,” Lovejoy said.

In the hospital in 1948, Lovejoy endured a process called a physeal arrest, which stopped one of his legs from growing to stay the same length as his other, shorter leg, which was affected with polio.

“I’m supposed to be 5-feet-9, but I’m 5-feet,” Lovejoy said, with his booming and infectious laugh.

It was his leg problems that eventually caused him to give up his lifelong passion of riding motorcycles four years ago. Lovejoy said he put around 250,000 miles on various bikes during his riding years, starting when he was 18 years old in 1956 with a 1949 Harley Davidson.

One of Lovejoy’s nine lives came during a riot at Weir’s Beach in 1965, when he was on his way to the motorcycle races in Laconia, N.H. and ran into a pack of Hell’s Angels.

The notorious motorcycle gang had a roadside stop blocked off only for motorcycles, which is how Lovejoy and his riding companions ended up in the fray. Lovejoy said that a 1957 Chevrolet containing a family somehow slipped past the Angels’ guards.

The Angels reacted violently, immediately overturning the car and throwing cherry bombs at it, eventually lighting the car on fire. He said that as soon as the car caught fire, it caused a stampede and a riot that sent 80 people to the hospital and prompted a response from the National Guard.

“When they set that car on fire, that whole herd of people started coming down the street like a stampede,” Lovejoy said.

Lovejoy has known hard work all his life, since growing up on his parents’ farm in Benton.

“My parents told me ‘we didn’t have you to look at, we had you to work,’” Lovejoy said.

At 84 years old, he still works baling hay whenever and wherever he is needed.

“Whatever’s ingrained in you from day one, it’s going to exude out one way or another,” Lovejoy said.

From there, he delivered newspapers as a young boy, before falling in with what is now the Lucas Tree Expert Co., trimming trees for power lines.

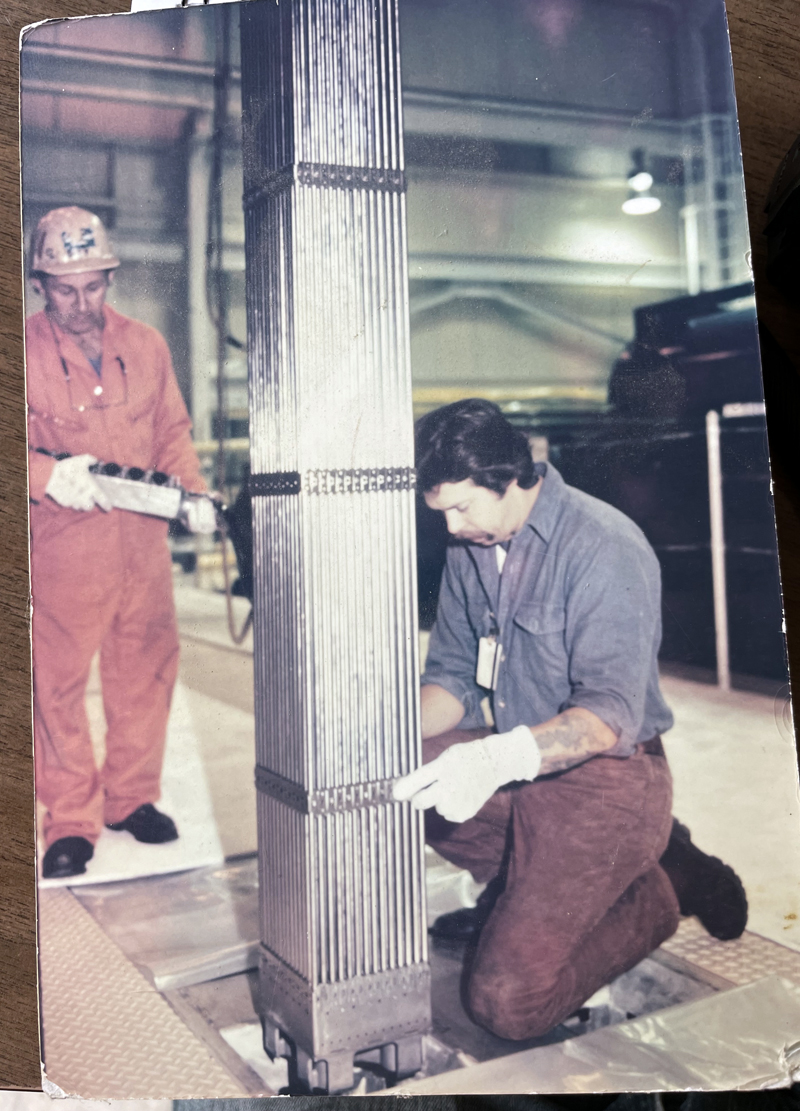

A picture of Alna resident Herman Lovejoy (left) working at the Maine Yankee power plant in Wiscasset. Lovejoy began working there full time in 1982 and took an early retirement when the plant closed in 1997. (Evan Houk photo)

Two of the three times Lovejoy had a gun pulled on him happened while trimming trees for power lines. One time was in the dead of winter when a man in loafers came up to him with a gun.

“This guy walked up behind me and he thought I was fooling around with his wife. And he had a pistol right on me. I said ‘No, the guy you want is up ahead,’” Lovejoy said with a hearty cackle.

Violence and the precarious nature of life seem to be running themes in Lovejoy’s life, even back to his ancestors. He cited his most famous relative, the anti-slavery newspaper editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy, who was born in Albion, killed during an attack by a pro-slavery mob in 1837, and is an icon at Colby College.

Lovejoy said he worked mostly union construction jobs and helped sporadically at the Maine Yankee and Mason Station power plants when they needed some work done on turbines or electric generators, like during a shutdown of the plants.

Eventually, he started working full time at Maine Yankee in Wiscasset in 1982 and bought a property in Alna. He has also worked at a cement plant in Thomaston, different paper mills, and at Bryant Steel Works in Thorndike, going wherever he could find work.

“My history is checkered,” Lovejoy said. “One year, I changed companies 14 times.”

It was at the paper mill in Jay where he and another employee accidentally ingested a discharge of chlorine gas. The other man did not make it, but Lovejoy did.

Herman Lovejoy’s second wife, Marcie Lovejoy, talked about the time in 2010 when he was having heart problems and she recommended he go into the hospital. Marcie Lovejoy, who works as a paramedic, put a cardiac monitor on him, but he refused to go to the hospital.

“How am I going to keep my stubborn if I don’t put my foot down once in a while?” Herman Lovejoy said.

He had a heart attack at 2 a.m. at LincolnHealth’s Miles Campus, but only had a 0.5% loss of heart function because he was so close to medical aid.

“I said ‘I’m never going to press that button!’ But I pressed the button,” Herman Lovejoy said of the nurse call button when he had his heart attack.

Upon moving to town in the early 1980s, Herman Lovejoy joined the Alna Fire Department at the urging of former Chief Austin Trask. He said he is the second longest-serving member after Trask’s wife, Coleen Trask.

He is currently the safety officer for the department and still responds to calls, mostly to perform traffic control.

In 2017, members of the fire department roped him into attending a surprise 80th birthday party with all his family in attendance at the Alna fire station by telling him a truck needed some work.

“That was a shocker of my life,” Herman Lovejoy said.

One of Herman Lovejoy’s beliefs is that everyone needs some help from time to time to accomplish anything.

“Everybody says they make it on their own. It doesn’t happen like that. Somebody pulled for every one of us to get where we are,” Herman Lovejoy said.

Another one his central beliefs sums up his devil-may-care attitude and life of constant and joyful work.

“We’re not here for a long time. We’re here for a good time,” Herman Lovejoy said.

(Do you have a suggestion for a “Characters of the County” subject? Email info@lcnme.com with the subject line “Characters of the County.”)