When I was in high school, my father was my principal driving instructor. I can still recall his first lesson:

“Marcus, I have observed three phases in the development of a driver. Phase one I call ‘initial apprehension.’ Stage two is ‘I’m invincible.’ The last stage is a safe and responsible driver. I would like you to make stage two extremely short-lived.”

As I have driven around the Midcoast area for the past few decades, I have observed (especially during leaf season) a fourth stage. I call it “final apprehension.” No doubt you have seen drivers in this stage. They are the ones who have a significant challenge making it all happen at the wheel.

I sometimes feel that our economic policymakers are also operating our economy in the phase of final apprehension. Myopia mixed with an odd brand of timidity and failure to act often characterizes our leaders.

One particular bit of myopia has caught my attention recently. It has do to with our focus on inflation or cost-of-living adjustment.

Back in the 1970s, the U.S. economy experienced a difficult bout of goods price inflation. By 1975, the U.S. Congress had acted to index Social Security payments to inflation. Many other labor contracts and longer-term production contracts also began to have inflation-adjustment clauses added to them.

On the surface, this sounds like a prudent policy. And indeed it is, for a while. But odd things happen when our gaze is fixated on the cost of living and we fail to observe the many other things going on around us. In fact, adjusting for inflation alone can create huge distortions when used over several decades.

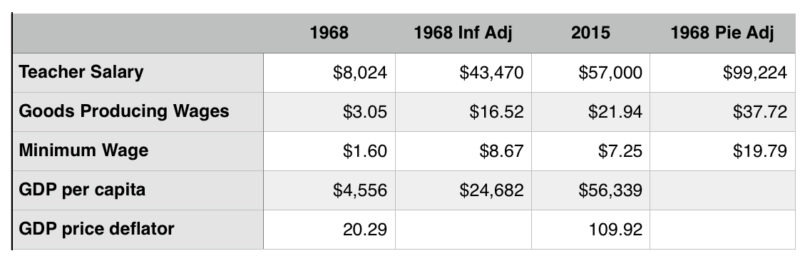

I have illustrated a few examples in the accompanying chart. In the chart I compare 1968 to 2015. In the first column, I show the median annual salary of public school teachers, the average hourly wage of goods-producing workers, the minimum wage, and GDP (total economic output) per person for the year 1968. In the second column, I show the 1968 levels adjusted to 2015 dollars using the GDP price deflator, the economic series used to adjust GDP for price inflation. The third column shows actual 2015 levels.

Note that in 2015, school teachers’ actual pay exceeded their inflation-adjusted 1968 salaries by more than $13,000. Workers who produce goods were likewise paid in 2015 in excess of their 1968 inflation-adjusted rate. Those who earn minimum wage fell back a bit, from an inflation-adjusted level of $8.67 to $7.25.

But this is in no way a complete picture of what is really going on. Take a glance at the row titled “GDP per capita.” Notice that 1968 GDP per person adjusted to 2015 was $24,682. But actual 2015 GDP per head was more than twice that at $56,339. What happened? The U.S. economy has become much more prosperous. Output per person has more than doubled since 1968. We have learned how to make many more things with our labor force, capital stock, and natural resources.

Now consider the three measures of income for school teachers, goods producers, and minimum wage earners as shares of a total economic pie rather than absolute quantities that must be preserved against inflation.

The final column of the chart shows what these three remunerations would have (or should have) been if teachers, goods producers, and minimum wage earners had retained in 2015 the share of the economic pie they had enjoyed in 1968. Note that these salary and wage earners have lost significant ground in their share of our economic prosperity. Rather than earning $99,224, teachers earn $57,000. Rather than earn $37.72 per hour, goods producers receive $21.94. And rather than earn nearly $20 per hour, the minimum wage is stuck at $7.25.

The same is true for most types of workers. When we focus on inflation, and ensure that social security recipients, or school teachers, or officers of government, or any other workers receive only cost-of-living wage increases, we also ensure that they do not participate in the productivity gains which accrue over time — productivity gains they helped to produce.

As such, where has the rest of the pie gone? Who has collected the large portion of the great prosperity we have experienced in the U.S. economy? And why do we hear from certain politicians that we cannot afford this or that program? I leave these questions as homework for our readers.