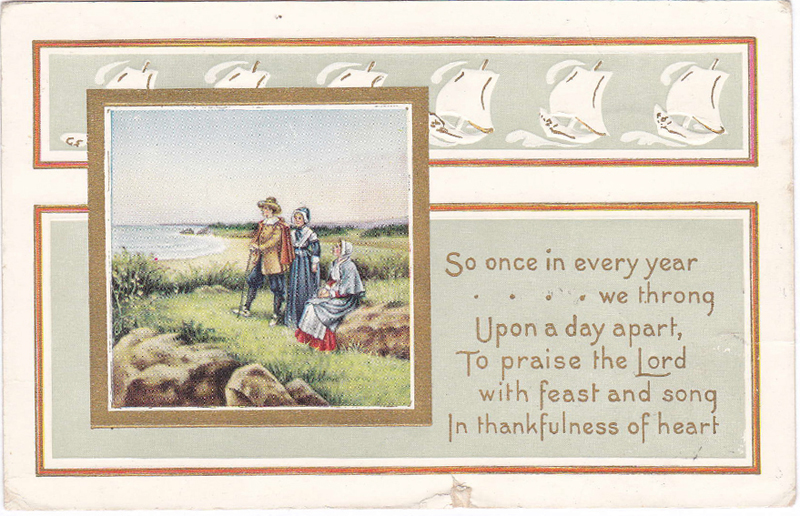

This postcard was mailed to Arlene Cole’s grandmother in November 1915.

When people from Europe came to settle in North America, they brought their holidays with them. Thus we still celebrate many, like Easter, Halloween, and New Year’s Day, as they did in the old country. But there is one holiday that is ours. Thanksgiving is purely American.

The first Thanksgiving in America was called into being by Gov. Bradford of the Plymouth colony in the autumn of 1621 in gratitude for its first harvest in the new world.

Like the postcard that was mailed to my grandmother in 1915, we think of the Pilgrims as women with their bonnets and wide white collars, and men with their brimmed hats and shoe buckles. But this is a stylized picture. They really were a mixed and ill-assorted group who had no special training for living in a new world. The Separatists who withdrew from the Church of England were known as “saints.” The adventurers who came with them, known as “strangers,” were in name or by profession members of the Church of England. The third group, the crew of the Mayflower, were a group of laborers from a different level of society. It has been just the wish of generations, as time has gone by, to make the group look like not what they were, but what we would like to picture them being.

We have all read about how the pilgrims arrived at Plymouth in December of 1620, how they suffered through the winter, and how nearly half of them died. But when the Mayflower sailed back to England in April, not one of the remaining Pilgrims was on the boat. Though many may have waved farewell with grave misgivings, they had adopted the land and they set out to make it a permanent colony. Proof of their success was their celebration that fall.

I got much of my information on the first Thanksgiving from the book “Mayflower,” by Nathaniel Philbrick. The feast was probably held in late September or early October. This would have been the time when the Pilgrims had completed their harvesting of corn, squash, beans, peas, and barley. With their barley, it was now possible to brew beer. They had an unlimited amount of venison from the forest. The men had gone to the harbor to shoot the migrating birds, mainly ducks and geese. They also brought back fish. There were striped bass, bluefish, and cod. They were set for the winter, so Bradford said it was time to rejoice.

The first Thanksgiving was not just a sitting-around-the–table affair. They say it lasted for days. The Pilgrims had made friends with the local Indians under Massasoit and they all came for the occasion. There were more of them than there were of the remaining Plymouth group and they brought deer and birds to add to the amount of food. There were wild turkeys around, so there were probably many of them on the menu, too. It soon became an overwhelmingly two-race celebration. Not having enough seating places, tables, or kitchen room, the celebrants stood, squatted, or sat on the ground and clustered around outdoor fires, where they cooked what they had brought to the feast. The Pilgrims did not recognize it as such, but one of the big things they had to be thankful for was the good fellowship they had with the natives.

Thanksgiving was held again in 1623 and then again at intervals, but it never became a yearly holiday for the Pilgrims. Others liked the idea, and through the years, President George Washington and President James Madison proclaimed a day of thanksgiving. For years, the custom was kept alive by proclamations from the various states.

Mrs. Sarah J. Hale is given credit for Thanksgiving becoming a national holiday when she presented the plan to President Abraham Lincoln and asked for his support. On Oct. 3, 1863, he issued an observance for a Thanksgiving Day on the fourth Thursday of November. Each year thereafter, the president proclaimed the holiday, which was celebrated by custom on the last Thursday of the month.

In early days, Christmas Day was very little noticed. Until the Civil War, according to Richard Shenkman in his “Legends, Lies & Cherished Myths of American History,” Christmas was hardly celebrated. Retailers took no notice of it. The day meant little to the Pilgrims. In fact, in 1659 a law was passed in Massachusetts Bay Colony against celebrating Christmas.

In 1870, the United States Congress established Christmas as a national holiday for the first time. The Civil War had been so terrible, people were looking for a peaceful family holiday. Christmas, as we know it, blossomed. Each year we add something new to our celebrating.

As Christmas became a widely celebrated holiday, it was felt that Thanksgiving and Christmas were too close together to enjoy both thoroughly. To stretch the number of days between them, President Franklin Roosevelt reminded us of Lincoln’s proclamation and decreed that Thanksgiving Day should be the fourth Thursday in November. It has been that way ever since. The two holidays are still close together. Long before Thanksgiving Day, things are set up for Christmas. Our friends in Canada have solved this problem. They celebrate their Thanksgiving Day in October, usually on the second Monday.

Here in this rural area, a harvest feast was just the ideal holiday. Nearly everyone lived on the farm; families were large and tended to cluster together. By November, gardens had been harvested, and carrots, onions, parsnip, turnips, pumpkins, and squash stored away in the cellar. Sauerkraut had been made. Corn, peas, and beans were canned and on the shelves. Apples had been picked and a trip had been made to the cider mill to get cider for drinking and to turn into vinegar for preserving.

There was not much meat on the family menu. Every family had a pig that was slaughtered in the fall as the weather got cold. It was smoked, pickled, and canned, with parts hung up in the freezing shed to be cut off for meals. The fat pork was saved to cook with the beans that were always baked, with brown bread, for Saturday night.

November became deer-hunting season, and getting a deer was more than a hobby. Many families depended on this extra meat, even having it at their Thanksgiving meal. Almost everyone had hens for eggs and an occasional dinner. Cows were milked twice a day and the cream separated to make whipped topping and butter.

We had cranberries down in the marsh. They were a pain to gather. We would put on long pants and boots and, with our buckets, head to the swamp. The cranberries grew in the marsh grass, which was sharp on our fingers. But little by little, we would be able to fill our pails. We spread the cranberries out, upstairs, in an unused room, and they would be cooked through the winter.

The harvest being ended and the winter prepared for, rural folks, then, had a good reason for Thanksgiving. We never had turkey for Thanksgiving, but one of our roosters. I came across a book, “Speaking of Maine,” with selections from writings by Virginia Chase, who lived on a farm for some years in Edgecomb. They did not have turkey for the big day, either, but chicken. She wrote of the “chicken that graced the head of the table.” Chicken, rooster — it was all good eating. Traditionally, there was plum pudding and pumpkin pie for dessert. Remember the poem by Lydia Maria Child? “Hurrah for the fun. Is the pudding done? Hurrah for the pumpkin pie!”

I remember one year we went to my aunt and uncle’s for Thanksgiving. My aunt had spent much of the morning tending over the plum pudding. Made of suet, raisins, currants, etc. and steamed, it had been a tradition for Thanksgiving Day for generations. My cookbook calls it a truly festive dish but then adds that a slow, six-hour cooking is necessary. She served it at the close of her meal, with the pies. My father, being a thoughtful adult, took some and praised it, but we kids preferred the pumpkin pie. She looked at the small amount of pudding eaten and thought of all her hours of work and said, “I am never going to make another plum pudding.” And she never did.

Like plum pudding, times and customs were changing. Turkeys became the big item. Often, Thanksgiving is referred to as “turkey day.”

Most of us no longer live on the farm. Apartments are small. Many women work away from home. We must buy everything we eat for the holiday. Families are much smaller and many live far apart. Even a turkey takes hours to roast and there are a growing number of people who no longer eat meat. If the children can’t make it home until Christmas, it could be a lonely dinner for an older couple. Some feel it is easier to “go out” for Thanksgiving dinner. With all the full-colored ads we are certainly tempted — no dishes!

I had my Thanksgiving dinner this year at my older daughter’s home. We had turkey with all the fixings. And pie — pumpkin and apple with ice cream. It was a nice day relaxing together.

Whatever you did, I hope you had a nice day, too. Like the Pilgrims, we have a lot to be thankful for.