The settlers left their homes and headed west. (Photo courtesy Newcastle Historical Society Museum)

Although Sheepscot was settled as early as 1630 and became a part of the town of Newcastle in 1753, interior Maine was much slower in settling. Trouble with the Indians and the French discouraged new settlers, and the shipbuilders on the rivers and shore and the men who took those ships to all corners of the globe kept people oriented to the sea.

Thus it was that during the war between Great Britain and France under Napoleon, the people here received a deathly blow.

In about 1804, problems began to cause great concern on what were the rights of a neutral country. Britain and France were in bitter combat and tried to strangle each other, and in the process attacked our ships and our neutral commerce suffered. We were a young nation and too weak to defend ourselves against both England and France.

Decrees, orders-in-council, and regulations followed one after the other. In 1807, the Embargo Act forbade American ships from clearing for foreign ports; foreign vessels were forbidden to land goods in the United States.

In 1812, we declared war on Great Britain. Many a company was doomed. Many a sailor was put out of work.

This same war that dealt a blow to commerce on the coast of Maine opened up land in the west. Here, “west” meant the Ohio area. The Indians were gone. There were vast acres of land not being claimed by anyone. The soil was good — much better than the rocky soil we have along the coast. Money was flowing freely. Why not go out and get some of the benefits?

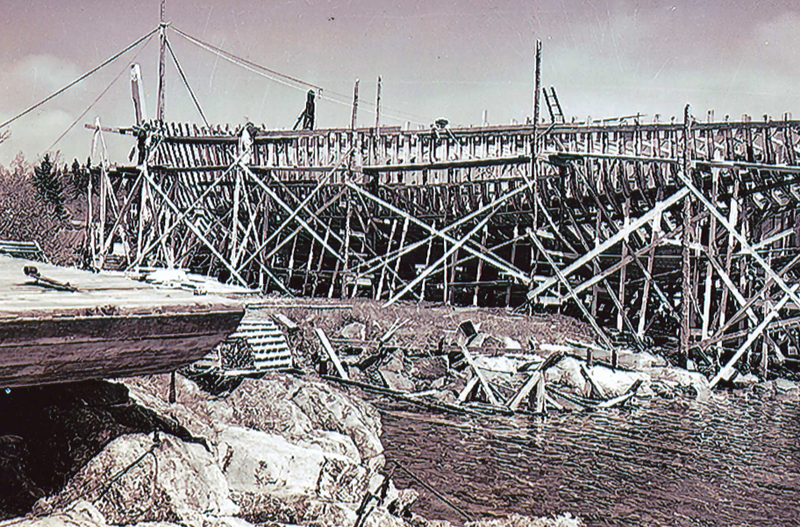

Building boats and sailing them was a way of life here on the Maine coast. (Photo courtesy Newcastle Historical Society Museum)

By coincidence, the weather played a large part in this exodus. According to David Ludlum in his “New England Weather,” 1816 was a cold summer. It is remembered in history as “1800 and froze to death.” There was snow in June. On July 8 and 9, a month later, frost was recorded in low places. It was 44 degrees at sunrise in Waltham, Mass.

With the snow and cold of June and July, there was a severe drought all summer. Then came a killing frost in September. All this combined to cause failure of crops, with a shortage of rations for man and beast. This gave one more reason for the western migration that followed that spring.

It is estimated that about 8,000 people left Maine for the Western Reserve, as it was called. Elizabeth Coatsworth gives a good description of conditions in her “Here I Stay.’’

Coatsworth’s fictional story of a small settlement, with Margaret as the main character, tells of how most of the families were inspired to leave for Ohio and made preparations. Margaret would not go, but she watched her neighbors give away treasures to friends so they would know who had them. They sold all they could, then held an auction. Not only was everything auctioned off, but the auction worked backward in that the group auctioned their grandparents or great uncle off, to be cared for by someone who would remain, as he was doing too poorly to make the trip.

Then one morning in May, Margaret and her remaining neighbors heard a sound on the road toward the east — horses’ hoofs on the hard earth, the lowing of oxen and the creaking of the wagons they were pulling, human shouting and the bleating and cackling of the farmyard animals. Some, who had no wagon, pushed wheelbarrows piled high with all they owned. A few carried sacks on their backs and would walk to Ohio. After their passing and the dust had settled, Margaret and her remaining neighbors turned away.

They would never see their friends again.

The 1840 gold miners took this same “go west” attitude. The only difference was the gold miner man headed west alone. In the early 1816 to 1817, the entire family left and they never returned. There are people in Ohio today who trace their roots to Maine.