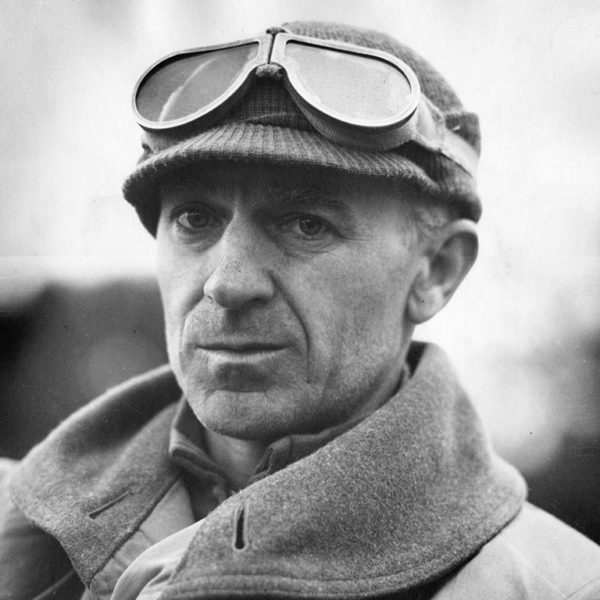

Ernie Pyle (Photo courtesy Don Lopreino)

Pulitzer Prize-winner Ernie Pyle was one of many American war correspondents during World War II, but he was easily the most famous because of what he wrote and how he wrote it. His columns were syndicated across the country and brought home the tragedy of war and those who fought and died in it in a way that no other reporter did.

He is also the subject of a new book “The Soldier’s Truth,” by David Chrisinger, from which some of the following material has been drawn.

Pyle was born on Aug. 3, 1900, but, considering his later presence close to the action on the front lines during the Battle of Britain and the Invasion of Normandy and in places like North Africa, France, and Italy, he might not have expected to live very long. Sadly, he was right. He was killed by a Japanese machine gunner on April 18, 1945 near the island of Okinawa in the Pacific.

Pyle wrote many columns. He usually focused on soldiers for whom battle was a daily challenge and the personal loss of friends and fellow comrades was all too common. Occasionally, Pyle returned home on leave, but he always seemed anxious to go back to the war. He never appeared fully comfortable being safe and protected while others fought and died in battle.

Pyle never forgot that when duty calls, it must be answered. There were stories to tell, columns to write, witness to bear about the personal face of battle, including the loss and sacrifice lest they be forgotten – all solemn obligations that had to be fulfilled.

Pyle’s best-known and most widely reprinted column at the time was about the death in Italy 1944 of Capt. Henry T. Waskow, of Belton, Texas, a young officer and company commander in the 36th Infantry Division. Like many others under fire at the time, Waskow was taking cover during an artillery barrage, but death in battle can be sudden, without time to prepare or react. One moment Waskow was alive. The next moment he wasn’t – his life suddenly taken by an exploding mortar shell.

Pyle’s language about the captain’s fate is so moving and timeless that what he described almost 80 years ago – a little more than a year before his own passing – could have happened yesterday. What follows is an excerpt from that remarkable account:

“I was at the foot of the mule trail the night they brought Capt. Waskow down. The moon was nearly full and you could see far up the trail, and even part way across the valley. Soldiers made shadows as they walked.

“Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules. They came belly down across the wooden back saddle, their heads hanging down on the left side of the mule, their stiffened legs sticking awkwardly from the other side, bobbing up and down as the mule walked.

“I didn’t know who that first one was. You feel small in the presence of dead men, and ashamed at being alive, and you don’t ask silly questions.

“Then a soldier came into the cowshed and said there were some more bodies outside. We went out into the road. Four mules stood there in the moonlight in the road where the trail came down off the mountain. The soldiers who led them stood there waiting.

“’This one is Capt. Waskow,’ one of them said quietly.

“Another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the dim light, for everybody was grimy and dirty. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive.

“‘I’m sorry, old man.’

“Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tender, and he said: ‘I sure am sorry, sir.’

“Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there.

“And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

“After that the rest of us went back into the cowshed, in the shadow of the low stone wall. We lay down on the straw in the cowshed, and pretty soon we were all asleep.”

Perhaps in some way, Pyle viewed the captain’s death as a precursor of his own. He was likely aware that the odds against survival in combat always increased the longer one is exposed to danger. One day without warning, time ran out for Pyle, in a faraway country in a war that he must have known was nearly over.

In many ways Pyle’s legacy is his power of expression and his ability to inspire a worldwide readership that has lasted over many years, and is still relevant and poignant which is why his columns can still be found on line and in print, unaffected and undiminished by the passage of time.

While Waskow is only one of the more than 7,000 American soldiers buried at the Sicily-Rome cemetery in Nettuno, Italy, he is by far one of the best known, thanks in large part to what Pyle so memorably described – the deeply human side of grief and suffering, the sorrow, regret, loss, and even love amid the awful violence of war.

(Don Loprieno is a lifelong student of history and education. He lives in Bristol.)