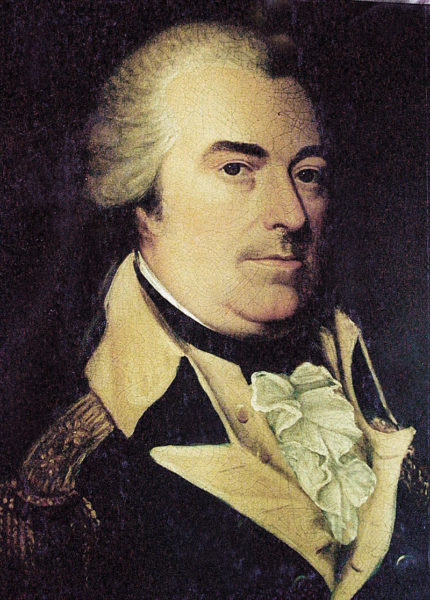

Born in 1745, the former Pennsylvania tanner, General Anthony Wayne, was 34 years of age when he commanded the American forces at Stony Point. (Photo courtesy New York Historical Society)

It happened during the American Revolution. Independence had been declared, but far from achieved with no end in sight. At 12:20 a.m. on July 16, 1779, a small but important battle occurred on the Hudson River.

Its anniversary will no doubt be little noted anywhere except the ground on which it was fought, now a historic site which this writer had the privilege to manage for nearly a decade. To those who struggled there, however, the midnight attack on Stony Point was all too real, epitomizing what has been called the human face of war – ordinary people reacting to extraordinary circumstances, sharing the same frailties and attributes common to us all.

Stony Point was one of two fortified peninsulas that bracketed the Hudson River, 12 miles south of West Point and approximately 25 miles north of Manhattan. This military and commercial waterway separated New York from New England. Whoever controlled it, British or American, enjoyed an important strategic advantage.

On a dark and windy night, the American Corps of Light Infantry, led by General Anthony Wayne and armed only with unloaded muskets and fixed bayonets to avoid detection and preserve the key element of surprise, stormed the defenses. As they approached the peninsula from the west or landward side, they formed two attack columns, and wore pieces of white paper in their hats to avoid confusion in the darkness.

One column would proceed around the peninsula on the south, while a second column would sweep around the north. Two companies of North Carolinians were positioned in the center to fire shots and divert the British defenders, a tactic that would draw Crown forces to what proved to be the wrong place – the middle of the British defenses instead of the flanks.

General Wayne commanded the south column made up of 700 men from Connecticut, Massachusetts, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. These troops waded through the shallow waters of the bay. Meanwhile, the north column, 300 soldiers from Pennsylvania and Maryland commanded by Colonel Richard Butler, entered along the other shore of Stony Point, basically paralleling the advance of Wayne’s south column.

Each column was preceded by 20 picked men comprising the “forlorn hope” – volunteers who would meet the brunt of British resistance and be exposed to the greatest risk.

In less than 30 minutes, the heaviest fighting had ended with the capture of the British commander, Lt. Colonel Henry Johnson. By 1 a.m. the fort and garrison were in American hands.

After destroying the fortifications, the Americans removed enemy material and weapons including 14 cannons and marched off more than 500 prisoners. By October of that year, shortages of men and supplies compelled the British to leave the area for good, giving up their goal of controlling the Hudson River and the military advantage of a vital maritime highway.

Their focus was now directed toward the American south, but that ultimately proved to be a fatal rendezvous for British forces at a sleepy Virginia village called Yorktown.

Stony Point was an important step down that road to England’s ultimate defeat. The attack established the fighting ability of the Continental Army, and proved to be one of most dramatic exploits in the annals of military history. Another result occurred that indirectly established the precedent to a long-standing American military tradition that still exists today- the creation of an individual medal for exceptional courage, sacrifice and devotion to duty.

When news of the Light Infantry’s victory reached Congress, it decided “That a medal, emblematical of this action, be struck: That one of gold be presented to Brigadier General Wayne, and a silver one to Lieutenant Colonel Fleury and Major Stewart respectively.”

These were not the first Congressional medals. Prior to 1779, only two had been conferred by that body – one to General Washington for the evacuation of Boston by the British in 1776; and one to General Horatio Gates for the defeat of Burgoyne at Saratoga in 1777. From this point on, however, medals would be awarded for meritorious conduct in military action. By the end of the Revolution, the second longest war in American history, only 11 medals would be issued during the eight long years of conflict and sacrifice.

The midnight assault of Stony Point, involving less than a half hour of combat, was the first of only two battles for which three medals were awarded. The medals represented not only the bravery of the soldiers themselves, but also the country’s increased pride in a military force that could launch a daring, well-planned assault that equaled the highest standards of trained professional soldiers.

For their actions during the nighttime assault, three American Light Infantry officers – Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, Lt. Colonel Francois de Fleury, a French volunteer, and Major John Stewart – were awarded medals by Congress. Each decoration was individually designed and cast. De Fleury’s medal was the only one awarded to a foreign officer.

The other recipients during the war were Henry (Light Horse Harry) Lee for Paulus Hook, N.J. (1779); Daniel Morgan, John Eager Howard, and William Washington for Cowpens, S.C. (1781); Nathanael Greene for Eutaw Springs, S.C. (1781); and John Paul Jones for the victory of the Bonhomme Richard over HMS Serapis, off the English coast (1779).

The Stony Point medals, however, were the first awarded for courage in battle and set the example for others to follow throughout our country’s future wars. Though not identified as such, they were arguably the first Medals of Honor.