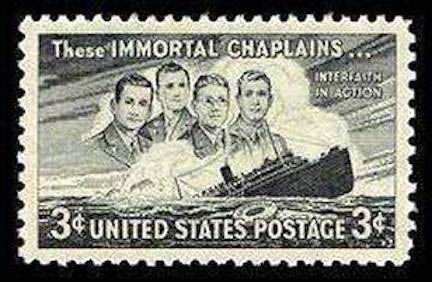

A special postage stamp issued in 1948 commemorates the sacrifice of the four Immortal Chaplains. (Photo courtesy Don Loprieno)

Last Friday, Feb. 3, an anniversary occurred that is now almost totally forgotten except by those who knew about it at the time. It is only a footnote in the history books, if it is mentioned at all. Unfortunately, it is not taught in schools.

The result is that many who should know about one of the most poignant examples of brotherhood and sacrifice are unaware it ever happened.

It was 12:55 a.m. on Feb. 3, 1943, when a torpedo smashed amidships into the Dorchester, an American troop carrier, and quickly sent her to the bottom of the Atlantic off the coast of Greenland. The Dorchester had been launched in 1926. It was 367 feet long, and weighed 5,680 tons, relatively little for her length. She was designed as a luxury passenger ship, but in March 1942, she had been refitted to carry military personnel. On Jan. 22, 1943, she set sail on her last fateful voyage.

The Dorchester’s destination was American bases in Greenland, and her route would take her from Staten Island, N.Y., along the northern coast of the United States, and then, after a resupply stop in St. John, Newfoundland, through the icy waters of what was called “Torpedo Junction,” named after “Tuxedo Junction,” a popular tune of the day. It was a very dangerous area because of the number of German submarines who were taking a fearful toll of American vessels, including the Chatham, one of the Dorchester’s sister ships, which was the first American troopship sunk in World War II.

With that and other disasters in mind, the Dorchester traveled in a 64 ship convoy that followed a zigzag course for protection. By Jan. 29, when the Dorchester was about to leave St. John, the convoy had been considerably reduced in size. Now it contained two freighters, the Biscaya and the Lutz, and three U.S. Coast Guard escorts: the Tampa, a 240-foot heavy cutter, and the Escanaba and the Comanche, 165-foot cutters that had served as icebreakers in the Great Lakes before the war. All three were part of the Greenland Patrol.

The Tampa would sail about 5,000 yards in front of the Dorchester, which was bracketed by the Biscaya and the Lutz, while the Escanaba and the Comanche were deployed several thousand yards and slightly astern on the starboard and port sides. On board the Dorchester were 900 passengers and crew: 597 soldiers who would replace other military personnel who’d been in Greenland since Pearl Harbor; 171 civilians under contract to the War Department, and 132 crew members, including Navy, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine men and officers. Also on board were four army chaplains – Rabbi Alexander Goode, Father John Washington, and two Protestant ministers, Rev. George Fox and Rev. Clark Poling.

Speed and erratic movement, along with keeping in group formation, are essential defenses against submarine attack, but the Dorchester, even though it had a maximum speed of 14 knots, now had to slow to an average of eight, in order to keep pace with the cutters. In the mid-afternoon of Feb. 2, the Tampa, under the escort command of Captain Joseph Greenspun, radioed that submarines were in the area.

Tension was high, and the men were ordered to wear as much clothing as possible, including life jackets. The convoy also had to contend with gale force winds and mountainous waves. As the weather improved, a wave of relief swept over the storm-tossed ships, but their euphoria was short-lived. A German submarine, U-223, on its maiden voyage, fired three torpedoes, one of which ripped a hole from below the waterline to the top deck of the Dorchester.

Many were killed outright by the initial blast. Though the order to don life vests had been given earlier, only a few men had put them on. Now a struggle ensued to obtain what might mean the difference between death and survival. The four chaplains were on deck, trying to encourage and console the men, and passing out life preservers. When these were gone, they took off their own and handed them out too.

One witness stated, “I saw the chaplains clearly, standing at the rail of the ship minus their life jackets, urging men to leave the ship with disregard to their own safety.” Another said, “The last I saw of the chaplains, they were standing on the deck, praying. By that time the ship had capsized and was at a 45 degree angle.”

All four, Fox, Goode, Poling and Washington, went down with the ship. Like many others who perished, their bodies were never found. The greatest loss of life, however, was not the explosion itself. Two-thirds of the 900 men aboard the Dorchester were victims of hypothermia as they struggled to stay afloat in the freezing waters. Ironically, many more might have been saved if Captain Greenspun had not delayed rescue attempts until he was certain that the U-223 would not strike again.

Many who witnessed the heroism of the four chaplains and many others who’ve read about it over the years have been inspired by their devotion. In 1948, a special stamp was issued commemorating their sacrifice, and in 1961, the Congressional Medal of Valor, equivalent to the Medal of Honor, in addition to the Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross, was awarded to each of the chaplains. Their images now appear in a number of churches and synagogues throughout the country, including at the United States Military Academy in West Point, N.Y., and in a 2004 book, “No Greater Glory,” by Dan Kurzman, from which this account is largely drawn.

Historical events are sometimes important in themselves, but they achieve modern relevance when they transcend their own time and space and become applicable to ours. In the current age of media stars, instant celebrities, and incessant self-promotion, genuine heroes– those who give of themselves without the fanfare of public notice — seem to be in very short supply.

One need look no further than the Immortal Chaplains whose total dedication for the welfare of others was demonstrated 80 years ago last week – an act of personal sacrifice which, like all such deeds, reverberates far beyond itself and sets an example for us all.

(Don Loprieno is a lifelong student of history and education. He lives in Bristol.)