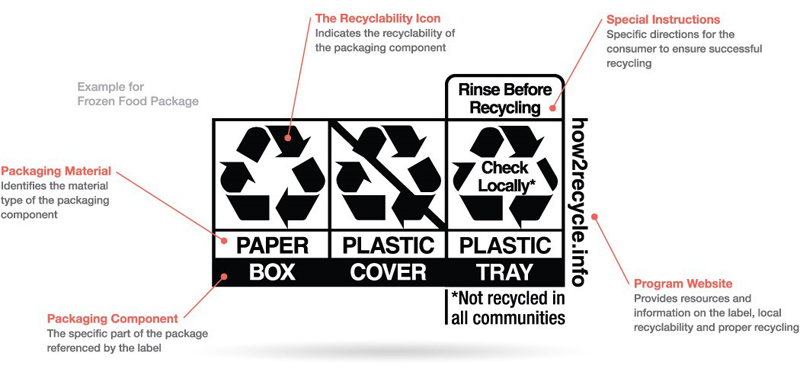

An example of a label for a multiple-component package from the How2Recycle website, how2recycle.info.

In examining a package to be discarded, have you ever felt confused about whether or not it can be recycled? Current recycling protocols place the responsibility for making such decisions on consumers. But merely affixing the chasing arrows symbol or printing the words “please recycle” on a package offers little guidance on how to do so. In some cases, claims of recyclability can be downright inaccurate.

In consequence, recycling rates remain lower than they might be. In Maine, for example, the goal to attain a statewide recycling rate of 50%, mandated in 1989, remains stagnant at just below 37%. A lack of clear and consistent labeling of recycling information on packaging contributes to this underachievement.

The innovative How2Recycle label, a trademarked system developed by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition and part of the 501(c)(3) nonprofit called GreenBlue, seeks to correct these shortcomings.

By paying closer attention to our packaged purchases, we have begun to notice the increasing presence of the How2Recycle label. Launched in 2012, How2Recycle has grown to include more than 250 companies, among them corporate giants such as Danone, Kraft/Heinz, Morton (salt), and Amazon. Vermont-based King Arthur Baking Co. is one of its most recent adoptees, having joined in November 2020.

At first glance, the How2Recycle label may appear complicated, because it has several sections dedicated to different purposes: 1) how to prepare the item for recycling, 2) how widely recycled it is and where it goes, 3) the material type, and 4) the specific component of the packaging to which the label refers.

After some familiarity, however, this label will provide the user with valuable information, like an item must be “clean and dry,” or that the cap or sprayer head should be removed before it can be recycled. This labeling system also evaluates collection availability in North America: whether the item is “widely recycled” (meaning greater than 60% of Americans have access to a curbside or drop-off location), recycled in some communities (20-60% availability), not recyclable, or recyclable only at specific drop-off locations (such as plastic bags or films that may be deposited at retail stores).

The How2Recycle label, moreover, provides recycling information about each component of the package. If, for example, a package consists of an exterior box containing a product in a plastic sleeve that rests on a plastic tray, the label has three corresponding sections that inform the consumer how each might best be disposed.

Examples of several How2Recycle labels from items in the authors’ homes.

Participation in How2Recycle is voluntary. Depending on its size, when a company decides to become a member it pays an annual flat fee, from $2,000-$7,500 per year. The company can choose to place the How2Recycle label on some or all of its packages. How2Recycle then conducts an individualized recyclability assessment based on a company’s packaging specifications before producing its label. How2Recycle also uses guidelines established by the Federal Trade Commission, the entity charged with regulating marketing claims around recyclability, to ensure that labels are not deceptive.

Why would a business voluntarily pay into a system that delegates their labeling to a third-party entity over which they have little control? Because membership in How2Recycle can help corporations meet their sustainability pledges by demonstrating a commitment to better recycling information on packaging, and help assure consumers that there is a level of independence and transparency to the labeling.

Folks at How2Recycle contend that transparently displaying this information is helpful not only for the consumer but also for the brand owner, because it serves to educate on good packaging design when they apply for each label.

A major criticism of the How2Recycle system is that it allows member companies to select the packages they choose to label. This offers participants the option to decline labels for non-recyclable packaging that might reflect negatively on the brand or a company’s sustainability goals. Some also argue that the threshold for determining the sought-after “widely recycled” designation is too low and suggest that accessibility by 80% or more of Americans would be more appropriate.

On the other hand, How2Recycle periodically reassesses and updates the packaging materials that it labels. In early 2020, H2R determined that both No. 5 and non-bottle-grade No. 1 plastics no longer met the threshold to be considered “widely recycled.” This downgrade had significant implications, since package labels had to be changed to the less desirable “check locally” designation and companies lost ground in meeting their sustainability goals. How2Recycle anticipates that both types of plastic will, at some point in the future, again qualify for the “widely recycled” label.

Falling below this threshold, on the one hand, is indicative of the woeful state of recyclability for many plastics in the U.S., an ongoing reverberation of marketplace upheaval since China’s policy change in 2018. However, the reassessment can also be seen as an indicator of credibility and independence for How2Recycle, since it readjusted, based on evidence, in the direction opposite the likely wishes of its corporate members.

Will the voluntary How2Recycle labeling system single-handedly rescue recycling in North America? Unlikely. But by offering succinct and credible label information for consumers, How2Recycle may have created a road map for more widespread, user-friendly labeling of packaging in the U.S.

(Mark Ward and Michael Uhl are citizen journalists investigating recycling and waste-management issues in Lincoln County. Mark, of Bristol, is a biologist. Michael, of Walpole, is a writer.)