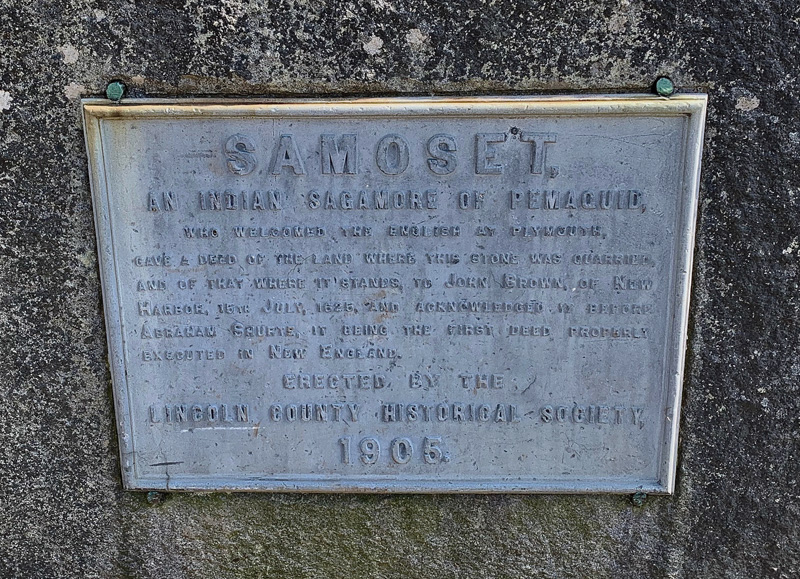

The plaque on the Samoset memorial in New Harbor. (Photo courtesy Christopher M. Leighton)

Last year, my neighbor Seymour Kagan and I approached the Bristol Board of Selectmen with a request. We noted that the Samoset monument would soon disappear under a thicket of vines and dead pine trees. The rescue of the monument required an intervention.

We contended that this undertaking is worthy of our attention because it provides a historic testament to the fact that the lives of the indigenous population and the colonists were intertwined. Indeed, the memorial reminds us that most of our ancestors were once vulnerable immigrants whose survival was tenuous and whose claims to the land were weak. Without an understanding and appreciation of this history, the struggles that defined this land and its inhabitants would slip into obscurity, and we would be destined to navigate the future with little awareness of where we came from. So we requested help for the rehabilitation of the monument.

Given the traffic on Route 32 and the steady flow of pedestrians en route to the Hardy Boat, the selectmen affirmed the importance of this local landmark and agreed to offer assistance.

A Bristol township crew promptly kicked into gear, cutting down and removing dead trees and underbrush. We then enlisted Hanley Construction to unload several truckloads of dirt into the hollow behind the monument. Kevin Steele deployed his machinery to smooth the surface and set the stage for Heather and Chris Leeman, proprietors of Maine Home Networking. They generously contributed topsoil and considerable labor to remove rocks and plant the hydrangeas and rhododendrons that the Kagans had purchased. The job of making the site beautiful and honoring New Harbor’s legacy was, in the Leemans’ words, “Simply the right thing to do.”

The monument commemorates Samoset, the Indian sagamore of Pemaquid, who welcomed the English at Plymouth and who allegedly deeded the land where the memorial rests to John Brown. The monument was erected by the Lincoln County Historical Society in 1905 and maintains that Samoset and Brown came to an agreement that constituted the first deed executed in New England. Of course, monuments often conceal as much as they reveal, and the Samoset monument is no exception.

Local historian Pete Hope is convinced that the events to which the monument points were more than likely a legal fiction. The notion that land was property, a commodity that people could own, buy, and sell, would have contradicted the sensibilities of the indigenous populations. Native peoples certainly recognized that land can be used, but it belongs to its maker.

When asked about the events enshrined in the monument, Pete Hope voiced a suspicion shared by most contemporary historians of this region. He surmises that John Brown’s ancestors fabricated the deed to give greater legitimacy to their claims to the territory.

The monument, therefore, points to a complicated and vexing history. The comity that the Samoset monument celebrates shrouds the bloody contestation that pitted early colonists against Native American tribes.

According to another local historian, Mike Dekker, we inhabit a region where colonists waged a form of warfare that amounts to attempted genocide. The land on which we now live was once the epicenter of the First Nations Wars.

The Samoset monument, therefore, invites us to ponder momentous events that stretch from a distant past into our own time. Does the current memorial falsify the past with a picture of ethnic and cultural harmony that never existed? Does contemporary historical scholarship necessitate a new and revised plaque?

One challenge is for certain: Justice requires a reckoning with a legacy that we have all too often been inclined to romanticize and misrepresent. Now as then we must find ways of living creatively and respectfully with diverse ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds. The monument challenges us to ask unsettling questions about where each of us came from and where we are going.

Therefore, thanks is in order to the collective efforts of our neighbors, the selectmen of Bristol, and local businesses for giving new prominence to this historic memorial, and for enabling this massive stone to speak of the unfinished work of forging a just democracy.

(Christopher M. Leighton, of New Harbor, served for 30 years as the executive director of the Institute for Islamic, Christian, Jewish Studies in Baltimore, Md.)