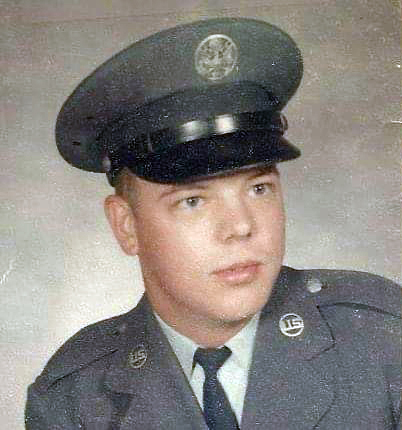

Raye S. Leonard’s father, Cal Stilphen, as a young Air Force private. (Photo courtesy Cal Stilphen).

I am the daughter and granddaughter of war veterans. My father served in the Air Force during Vietnam, and my maternal grandfather fought with the Army in World War II.

Like Bruce Poland noted in this week’s “Characters of the County” feature on the front page, veterans don’t talk much except perhaps to other veterans. Even then, I imagine they have a short-hand where silence takes the place of words; among veterans, they understand what is unsaid.

My dad enlisted when he was 18, served his Vietnam tour from 1969 to 1970, and came home to my mother and built a life for our family. He rose to the rank of master sergeant and got out in 1978 after a tour in Alaska when I was 7 years old.

I know this because I just texted him to ask, and not because he broadcasted it throughout my childhood.

Dad either told me once, or he told one of my kids (who told me), a story about how he was determined to join the Marines like his brother.

According to what might be legend, my uncle said if that’s what Dad planned to do, my uncle would shoot Dad right then and spare him the trouble of basic training.

The threat must have had some effect because Dad joined the Air Force instead. And we are all here to (not) talk about it.

I also have one memory. I came home from school one afternoon when I was in third grade and told Dad we learned about the Vietnam War.

He snorted and said, “It’s a war now? I thought it was a conflict.”

The sarcasm was completely lost on me, and of course, I had no historical context at age 9. But the memory stuck. Dad, who worked second shift at Bath Iron Works, stood in the kitchen of our Oliver Street duplex silently stirring SpaghettiOs for my after school snack on the stove, shaking his head.

I had (and continue to have) a finely tuned sense for when there’s more to a story than I am being told. But he said no more.

I was probably in college when I learned enough about the Vietnam War to understand what he meant about it being a conflict, not a war.

I also learned that veterans of that war in particular came home, not to confetti parades and hero status, but to rotten eggs hurled at them, along with insults and shame.

No wonder they don’t want to talk about it. War experience is a heavy burden, but I believe shame carries just as much weight.

My grandfather, Papa, never talked about his war experiences either, but he also didn’t talk about anything else, except to remind me to be a “good girl” and say my prayers.

I have just one story from his war time. I know I didn’t hear it from him. Likely, I overheard it, since I was an expert eavesdropper.

Papa was gone for five years and when he returned to the U.S., he landed in Boston. I have it that he hitched a ride to Bath, but perhaps he took the train.

Papa walked up Front Street following an old woman, headed home. He was surprised when this stranger turned up the walkway where his family lived.

He said to her, “Excuse me. Is this the home of the Cormiers?”

She turned to him, and after a moment of searching each other’s faces, Papa realized this stooped old woman was his mother, and she realized that the man before her was her son.

I can imagine the shock for my grandfather, to see his mother transformed by the uncertain years of war.

I imagine, too, the rush of joy and relief my great-grandmother must have felt to see her child again after so much time and so much change.

After all, the men who came back from war left as boys.

As the mother of mostly grown children, I can tell you that the child, the baby always remains in a mother’s heart, so to behold the adult version of the person you grew in your body is a quantum prismatic vision.

We know so much more about brain development now than we did when my 19-year-old father shipped out for Phu Cat in 1969.

Much of my graduate-level work in adult education was based on trauma theory, and trauma-informed practice. Indulge my lack of citations as I write from broad prior knowledge.

We know that the brain continues to develop until about the age of 26. We also know that developing brains are particularly sensitive to trauma.

I taught several veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in the mid-2000s at Southern Maine Community College. Many of them shared their war stories, or as I regard them now, their trauma stories.

Every single veteran of every single war has these stories, too.

Often they remain unspoken except to other veterans. But I imagine even that might hurt. It might be easier to try to forget by focusing on a career, family, or goals of all kinds.

I believe in the healing power of telling stories about what happened to us. But I’m a writer, and of course I’d feel that way.

Thankfully, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs recognizes the profound effect of post traumatic stress on both soldiers just returning from war and those who came home long ago. Veterans can access a range of support and treatment options for PTSD that just a generation ago was unavailable.

Storytelling may never be top shelf VA policy, but this Veterans Day as you say thank you, remember that behind those service stars is often a story that goes untold.