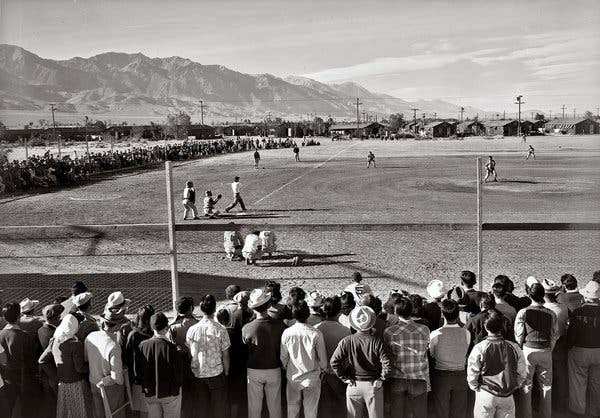

Baseball lifted spirits at Japanese internment camps during World War II, as shown in this photo by Ansel Adams.

Beginning with the 1942 season, professional baseball in the United States started to look very different. With Pearl Harbor having been bombed by the Japanese just a few months before, many were wondering if the major league season should continue as normal. The young men who played in the majors were already enlisting in the Army, and some thought it would be disrespectful to the war effort if the season were to continue like any other year.

President Franklin Roosevelt and MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis did not share these views, however, instead saying that baseball would provide the American people with “a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work.” Baseball during the war was played by old men and young boys, and the quality of play suffered (a far cry from the historic 1941 season), but it did provide weary Americans with a brief respite from the cloud of a world war. And for one particular group of people, baseball played an even bigger role in getting through the war years, although I doubt FDR was thinking about them when he was writing his now-famous “green light” letter.

I am, of course, talking about Japanese Americans, who were definitely on President Roosevelt’s mind when he signed a different, darker piece of paperwork, Executive Order 9066. This executive order forced over 100,000 Japanese Americans (most of whom were actually American citizens, despite being labeled “enemy aliens” by the government) into hastily built “war relocation centers” (concentration camps). These camps were cramped, with only 10 of them scattered throughout the western U.S., usually with 10,000 people at a camp.

The first thing these prisoners did after being relocated was to construct baseball fields, then they organized teams and leagues. One of the first of these camps, named Manzanar, was located near the Sierra Nevada. There were close to 100 different men’s teams, plus 14 all-women outfits. These teams often consisted of former pro players, and they played in front of large crowds of fellow prisoners. (What else was there to do?)

A couple years after this internment started, photographer Ansel Adams was allowed into Manzanar, but was forbidden from taking any photographs of the guards, searchlights, watchtowers, or barbed wire. Instead, Ansel captured the prisoners playing sandlot games. He soon found that baseball was the one thing that was keeping these people sane. George Omachi, who would become a major league scout after the war, is quoted as saying, “Without baseball, camp life would have been miserable,” which I find absolutely insane, because it implies that with baseball, life in an internment camp was not miserable.

Just like it was for the Americans outside these camps, baseball was an escape, something that took their minds off the reality of their situation. In a twisted way, these internment camps proved just how right FDR was when he thought baseball should continue. In major league cities, it was a useful way to keep morale up, and in these camps, it was an absolutely crucial tool used to keep a grip on one’s sanity and personal identity.

I first learned about this topic in a picture book titled “Baseball Saved Us,” by Ken Mochizuki, which tells the story of his father, who lived and played baseball at the camp in Idaho during the war. That is another amazing thing about this story. There were 10 different camps, but almost all formed baseball leagues independently. They were even allowed to play each other, eventually. Without any coordination, these people all built their own ballfields in the middle of the desert.

It’s almost like they were trying to show the people who put them in there just how American they were. One prisoner, Takeo Suo, said that “putting on a baseball uniform was like wearing the American flag,” which it is, in a very real way. Baseball, especially during the war, was, and remains, a very patriotic pastime. It was when it was played by soldiers overseas, or in the replacement player-filled majors, and it was patriotic when it was played by Japanese Americans in prison camps.

World War II gets a lot of airtime, and we talk about it as much as we can talk about any war, just about, but this is something that is rarely mentioned, and I think it should be. Those were Americans in those camps, and I think it’s important that people know what happened to them.

(Tiger Cumming is a 2020 graduate of Lincoln Academy and a huge baseball fan. He welcomes feedback on this column at ptcumming@gmail.com.)