Somerville artist Nathan Allard works on details of an egg tempera painting using a flying squirrel-hair brush he made himself. This tree painting will later be colored with glazes made from stones Allard grinds into fine pigments. (Elizabeth Walztoni photo)

Young artist Nathan Allard, of Somerville, works almost exclusively with materials in the landscapes he paints, from animal-hair brushes he makes and natural pigments he grinds to frames he constructs himself.

His egg-tempera paint materials include charred bones, ground rocks, dirt, and shells, applied with hair brushes from moose, flying squirrel, and more.

On a recent afternoon at his childhood home and studio, a former hunting camp built up into a two-story house, Allard and his childhood friend, Jeshua Soucy, of Belgrade, filmed a process video of the creation of a brush.

Allard demonstrated his process making brushes with feather quills — from the right wing of the bird, so that the curve fits over his right hand — and animal furs friends bring him. Some come from hunting trips and others from the side of the road.

Friends also supply him with chicken eggs for the yolks in his egg tempera paints and rocks he grinds. Once the rocks are ground, Allard mixes the pigments in seashells.

When the paintings are finished, he frames them with local wood, often from a friend’s sawmill in Palermo.

The only things he doesn’t make are the panels he paints on, but Allard is hopeful he might find a way.

“If there’s something I can’t make myself, I’m thinking about how to,” he said.

As a teenager, Allard was inspired by the art of Winslow Homer, Andrew Wyeth, and the Renaissance masters.

An exhibit at the Portland Museum of Art on Homer exposed him to the idea that art could still be a profession, and he began to practice in earnest, exhibiting artwork at the Skowhegan and Windsor fairs.

Allard said he was drawn to egg tempera because of the high level of detail it can achieve. He started painting in oil, but found it challenging because each layer has to dry before the next is applied, unlike egg tempera.

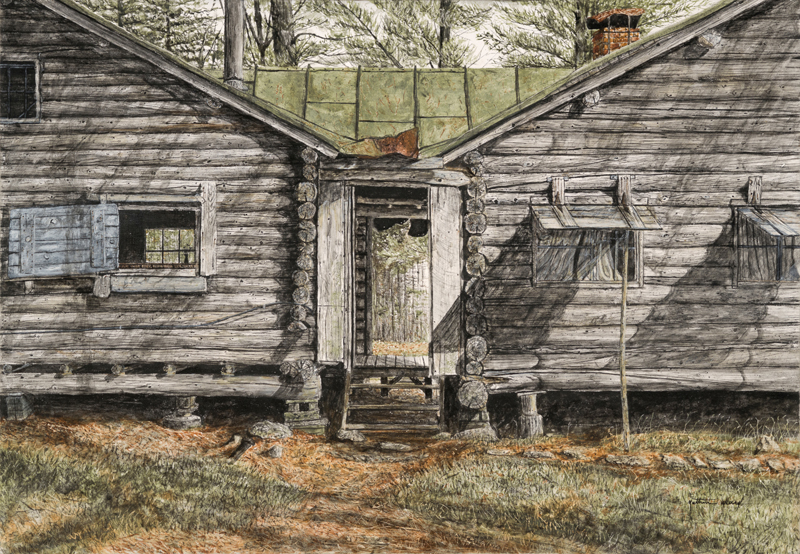

Somerville artist Nathan Allard’s painting “Breezeway,” the subject of an award-winning short documentary by the same name, was completed in five days using charcoal from the cabin’s wood, among other materials in the scene. Allard, who paints in egg tempera, uses all natural materials in his portrayals of the Maine landscape. (Photo courtesy Nathan Allard)

While practicing in his new medium, he learned that even commercial paints are often earth-based, Allard said, and he began exploring with dirt and rocks from his yard. He now has a rock collection in his studio which he grinds with a mortar and pestle.

“There’s some inner child in me that still likes collecting rocks. Kids do that a lot … but sometimes you can lose that wonder and start consuming what’s given to you instead of being choosy about it,” he said.

He said his work using natural pigments to create fine art is an unusual one today, as these materials are usually favored by artists making primitives.

Natural colors were the only materials available to the Renaissance painters he admires, however, and he said he enjoys researching the trade routes that made those works possible. He enjoys thinking about his own use of the landscape in a similar way.

“I like knowing what’s in my hands,” he said.

After some experimenting, Allard said he took a “cold-turkey” approach in his transition to natural brushes and pigments. One day, he threw out all his plastic brushes; he did the same with his tubes of paint.

He currently works part time as a timber framer, and spent five years as a carpenter, which he said taught him the work ethic a serious artist needs. Working on a home for a year or a year and a half, seeing a tree-filled lot become a house with someone moving in, taught him the long haul.

“I started from passion, but you have to hold onto a creative vision and have a backbone behind it,” he said. “Something simplistic, but enjoyable, takes a lot of work and stages.”

He said working on a scene is a process of adjusting details and watching the project evolve, and there is always movement inside a painting.

Allard painted from reference photos at first, but as he did with his plastic brushes and tubes of paint, he threw away the pictures one day and developed his observational skills.

The painting in progress this winter, of a tree on his property, began in the fall when the trunk was covered in pine needles. As the seasons changed, the image shifted into snow on the branches.

Allard is something of a chemist, but something of a physicist too. He said that the coarseness of the pigment determines the color; the finer he grinds, the lighter it appears.

Somerville artist Nathan Allard empties charcoal made from animal bones into a seashell to be mixed into egg tempera paint. The brush is made with a feather from the right wing of a bird to fit over Allard’s right hand. (Elizabeth Walztoni photo)

When he uses glazes of lighter pigments in more opaque layers, it reflects more light and attracts the eye.

Soucy said that Allard’s paintings are a physical representation of the scene.

“You’re literally looking at the shore, at the cabin, at the raven,” he said, when Allard uses stones from the shore, charred wood from the cabin, or bones from the raven to paint them.

Soucy is a self-taught filmmaker, and his brother Isaiah a self-taught composer. Together, the three have created several short films.

“We’re all pursuing something we’ve always done,” Allard said.

“A Painting from the Earth: Breezeway,” a 15-minute documentary released in December 2021, followed Allard as he worked on a painting of the same name over five days using pigments from the surrounding area including a piece of the cabin made into charcoal.

The documentary showed at the Maine Outdoor Film Festival, where it won best Maine film and best short feature.

Soucy’s filming of the brush-making process is not planned for a release yet, but gave him a chance to experiment with new close-up lenses.

Pointing to some of the completed works hanging in his home after filming, Allard explained how he composed the images to work with light both in the scene and on the physical painting.

“I like making something that’s academically good, but just made out of dirt,” Allard said with a laugh. “It’s more than just about the image. But also, it’s about the image.”

Allard’s art prints, “Breezeway” documentary, and more can be found on his website at nathanallardartist.com.