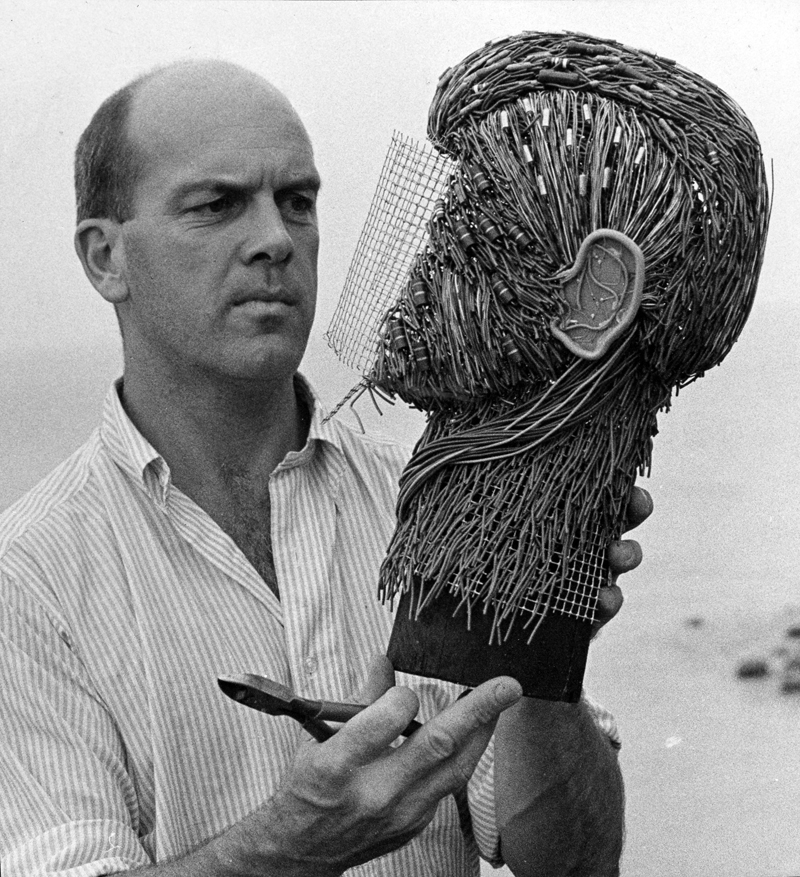

Ralph Moxcey in his Bremen studio. (J.W. Oliver photo)

Former U.S. Army Air Forces Sgt. Ralph E. Moxcey was on a boat crossing the Atlantic Ocean to France on V-E Day, May 8, 1945.

The 18-year-old from Waterville, fresh out of training to become a tail gunner on a B-24 bomber, was eager for combat.

Instead, he would become one of the first occupation troops in Germany. Though Moxcey didn’t see combat, the military transformed his life. He went to college on the GI Bill and became an art director for major advertising firms in New York City and Boston before retiring to Bremen, where locals know him as a sculptor and volunteer.

Moxcey was born on a farm in New Brunswick, Canada on July 3, 1926. His mother was in New Brunswick to visit her sister. She stayed too long and gave birth to her first of six children in the kitchen.

Moxcey grew up in Waterville. He was a young boy during the Great Depression. “Most of us were poor but we never knew it,” he said.

Moxcey’s father worked on the highway for the Works Progress Administration. His mother was a homemaker.

“We got our food from the state. We would go down to one of the schools and pick up margarine and potatoes and beans,” he said. “We were living pretty lean, but we were enjoying it. Life was fun.”

Moxcey worked from an early age. He was a newsboy for Grit and the Lewiston Evening Journal, a shoeshine boy, and a textile worker at the Hathaway shirt factory. He would work for the circus when it was in town in exchange for admission. He also had a knack for carving briar pipes with custom designs, with a local car dealer and a local doctor among his customers.

A young Ralph Moxcey before his departure for Europe and World War II. The note in the lower right-hand corner reads “your loving son and brother, Ralph.”

He was a junior in high school when he changed his birth certificate to enlist in the military at the age of 17.

“As kids, 17, 18, we were just going with the flow,” Moxcey said of his decision to enlist. “We just knew that we had to get into the service and fight for the country.”

As for his choice of a branch, Moxcey said, “I just wanted to fly.”

Moxcey went to boot camp at Keesler Army Airfield in Biloxi, Miss.

To avoid KP duty – military shorthand for undesirable kitchen work – he volunteered for the marching band, despite an utter lack of musical experience.

He said he could play the drums, but failed his audition. Then he said he could play the cymbals, and made the band. “That got me out of KP,” he said.

The soldiers would go into town on weekends whenever they could get a pass. Some of the officers ran prize fights, and to recruit fighters, they would offer a two-day pass to anyone who would step in the ring.

“I think I did pretty good,” Moxcey said. “You’d get walloped once in a while and you’d feel like your face wasn’t yours anymore.”

But boot camp wasn’t all cymbals and prize fights. Mississippi “was loaded with cockroaches,” Moxcey said. To keep the cockroaches from crawling onto their bunks, the soldiers would place the legs of their bunks into coffee cans with kerosene in them.

“But then they’d come up over the rafters and drop down in the bed,” Moxcey said.

“It was tough but it was good,” Moxcey said of boot camp. “I had never eaten as well. I’d never had so many friends.”

The military opened a “new world” to Moxcey, he said.

Ralph Moxcey (front left) with some of his military buddies during a cross-country train trip in the U.S.

If not for the military, he likely would have finished high school and gone to work at the Hathaway factory. In the military, several of his buddies were in college. For the first time, he started to think seriously about higher learning.

After boot camp came gunnery training, which took Moxcey all over the country – to Tyndall Field in Florida, Lemoore Army Air Field in California, and Walla Walla Army Air Base in Washington state.

Moxcey had wanted to be a pilot, or perhaps a bombadier or navigator, but the military had other plans.

“When we got down to basic training, they washed out 98 percent of our class and sent us all to gunnery school because they needed a lot of gunners,” he said.

In Walla Walla, “we did nothing but skeet shoot,” he said. The purpose was to train gunners to lead an enemy plane.

In an attempt to reproduce the challenges of gunnery on land, the gunners-in-training would shoot clay pigeons with a .50 caliber rifle from the back of a flatbed truck driving around in circles.

Ralph Moxcey (fifth from left) during training in the U.S.

Finally, Moxcey was on a boat full of soldiers on its way to Europe.

“I was excited. We were all excited. We were young kids,” he said. “We just wanted to get into a plane and have a few missions … We just saw it as an adventure.”

“We were all looking to fly – but that’s, again, being youthful and not really having too much thinking power,” Moxcey said. “I wanted to go into combat.”

On V-E Day, May 8, 1945, the day of Germany’s surrender, he was still on the boat.

The war in the Pacific would rage until August. “They were thinking maybe they were going to ship us off to Japan, but they didn’t,” Moxcey said.

Moxcey’s ship arrived in Le Havre, on the English Channel in northern France. The soldiers traveled by train to their base at Erding in southeast Germany, near Munich.

“We were the first occupation troops” in the area, Moxcey said. His primary duty was to run a sign shop for the base. He did go up in the B-24s a few times, but never flew a combat mission.

On leave, Moxcey attended some of the Nuremberg trials, including the trial of Hermann Goering, Adolf Hitler’s second in command. He visited the Dachau concentration camp and Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest.

There were lighthearted trips too. Moxcey and a tight-knit group of friends would go into Erding, Munich, or other nearby cities and towns. They went skiing at Zugspitze, a nearby mountain. They visited the French Riviera, Monaco, and Switzerland.

“We were really having a good time after the war,” Moxcey said. He and his buddies “were like brothers.”

The troops had friendly relations with the Germans in the area. “There was not a feeling of hate when we got over there,” Moxcey said. Many troops had German girlfriends.

Due to a postwar food shortage, the Germans couldn’t buy eggs, meat, or cigarettes, so the troops would bring food from the base or leave cigarettes as a tip at German businesses.

Moxcey received his honorable discharge after about 2 1/2 years of service. He received the Army Good Conduct Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

Upon his discharge, Moxcey returned to Waterville to finish high school, then studied advertising at the Cambridge School of Design in Boston. The GI Bill covered the full cost of his college education. “I never would have gone” to college otherwise, he said.

“The GI Bill was probably one of the biggest things that’s happened in this country,” Moxcey said. “It changed the whole face of this country, because kids that were on the farm back in some of these little, remote places could now go to college.”

After completing a four-year course, Moxcey set off for New York City with his portfolio in hand.

His first job was at a studio, working on a project for Kool and Life cigarettes. His salary was $40 a week. “I had no way to go but up, money-wise,” he said.

He bounced around for a while, working about seven jobs in less than two years.

His big break was landing a job at BBDO, a major national agency. He became an art director for BBDO in New York and later Boston before going on to hold the positions of art director and senior art director with other agencies.

Advertising “was an exciting business,” Moxcey said. The popular television show “Mad Men” was a fairly accurate depiction of the advertising business in New York City in the 1960s.

“That’s when I was down there,” he said, and “the three-martini lunch” was not just a creation of “Mad Men” writers. Neither was the technology – or lack thereof.

“We never had a computer,” Moxcey said. “There was no such thing.”

“As an art director, you had to draw everything, render everything, render your type,” he said. “The computer changed the whole business.”

The computer changed Moxcey’s career too. He worked on campaigns for Converse and Titleist, among other major brands, and with celebrity spokesmen like Johnny Cash and Ted Williams. But he is most proud of his work for Honeywell.

In 1964, Honeywell was attempting to establish itself as a competitor with IBM. Moxcey conceived a campaign that used models of animals sculpted from computer components. The ads billed Honeywell as “the other computer company.”

The campaign ran from 1964-1978, an unusually long lifespan for an advertising campaign. Some of the animal sculptures are now in the Computer History Museum in California.

Ralph Moxcey works on a sculpture for Time magazine.

Moxcey received numerous awards during his career, including Art Director of the Year from The Art Directors Club of Boston in 1974 and the L.E. Sissman Award, for combining a career in advertising with excellence in the fine arts, in 1995.

He also found time for community service. An Eagle Scout who once saved his 7-year-old daughter’s life with CPR, he was a Scouting leader and a volunteer firefighter for 23 years, and he sat on the boards of charitable organizations.

Moxcey retired from the advertising business in the mid-’90s and moved to Bremen about 15 years ago.

He and his wife, Wendy Moxcey, had attended a show at the former Round Top Center for the Arts in Damariscotta, and the center’s classes and events attracted them to the area.

A man of many hobbies and talents, Moxcey had started making wildlife sculptures while working in advertising. In Bremen, sculpting became his focus. He works in bronze, fiberglass, stone, and wood. The late Round Pond sculptor Don Meserve was an early mentor.

Ralph Moxcey uses an electric grinder to shape a wooden beaver sculpture in his Bremen garage. Some of his previous sculptures are on the shelves beside him. (J.W. Oliver photo)

Moxcey uses his talents as an artist to give back to the community. He has made signs for The Carpenter’s Boat Shop, of Bristol, and the Central Lincoln County YMCA, of Damariscotta, as well as illustrations of animals for the Y’s child care center in Nobleboro. He has repaired the Civil War monument at the Bremen Union Church and restored signs for the town of Bremen.

A father of three and grandfather of six, he stays extraordinarily active at 91. He credits his good health to diet and exercise. A lifelong fitness enthusiast, he works out at the Y at least twice a week.

He enjoys fly-fishing and goes on a whitewater canoeing trip every spring with a group of friends.

He is an active member of the American Legion post in Damariscotta and regularly attends a monthly gathering of veterans at Chase Point.

Last spring, Moxcey and three other Lincoln County veterans traveled to Washington, D.C. with Honor Flight Maine. Moxcey was the grand marshal of the Memorial Day parade through the Twin Villages this year.

About 20 years after Moxcey’s discharge, one of his friends from the service suggested a reunion. The six old war buddies had an annual reunion for many years thereafter. “They’re all gone now except for one guy,” Moxcey said.

Moxcey said the military taught him a number of important lessons. The value of camaraderie and friendship was among the most important. “Take advantage of what’s available to you and give of yourself” was another.

“You have to give of yourself to get anything back,” he said. “And if you don’t get anything back, so what? You have to feel good inside too.”