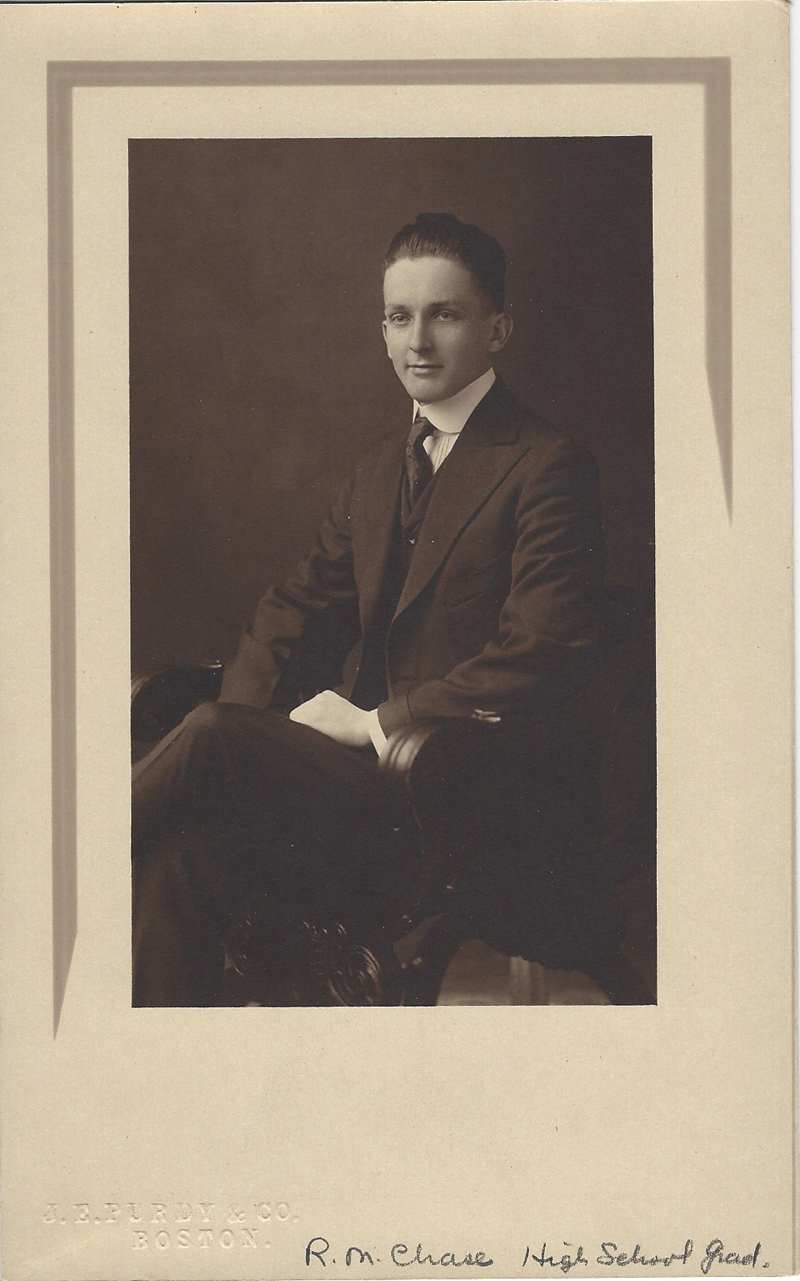

Roscoe Moses Chase at the time of his graduation from high school. Chase would go on to fight in World War I. (Photo courtesy Mary Ann Chase Vinton)

A century ago, on June 10, 1918, a 24-year-old farmer from Sheepscot named Roscoe Moses Chase was wounded while fighting Germans at Belleau Wood, about 50 miles east of Paris. A pivotal battle of World War I, Belleau Wood is a prominent piece of Marine Corps lore.

Pvt. Chase was my grandfather. Though he lived to old age, most of what I know about his wartime experience has been pieced together only in the last four years, amid the centennial of a devastating war that came to an end 100 years ago this Sunday.

My grandfather carried lifelong scars from his combat. One of the few surviving artifacts of his service is a tag that was affixed to his toe in the field hospital where he was treated for his wounds. A morphine dose was given. Injuries were scrawled down, firstly a gunshot wound. Some of the text is illegible.

“G.S.W. back + left side between 6 + 7 ribs non penetrating … 430 + 5 p.m. by shrapnel. Large gaping wound below lower angle left scapular. Non penetrating. Wound clean. … dressing applied …”

The tag, along with some medals and photos, remains in the possession of my mother, local resident Mary Ann Chase Vinton. She can also describe burns on his back from gas and shrapnel that remained in his body until his death in 1978. She was a physician working at Miles Memorial Hospital in the 1970s when her father got a respiratory ailment. That prompted a chest X-ray that revealed shrapnel scattered across his chest.

By all accounts, he rarely spoke about the war. Upon his return he became an electrician in Boston. He married fellow Sheepscot native Dorothy Carney and cared for his family’s ancestral home on Dyer’s Neck in Sheepscot. Known as Two Rivers Farm, it passed out of our family in 1961. It burned to the ground on May 12, 2016.

Recently our family has made an effort to recover more facts about my grandfather’s involvement in a war that killed nearly 10 million soldiers and reshaped global order. We obtained documents from the National Archives and studied newspaper clippings, memorials, and family mementos. Mysteries remain, but we learned a lot.

In September, our family took a trip to France to visit some of the famous battlefields along the Marne river. The trip, led by British historians, was organized by The National WWI Museum and Memorial. We saw trenches, tunnels, and, behind museum glass, rusted ordnance and bullets. At Belleau Wood we were able to walk in my grandfather’s boot steps.

The monthlong Battle of Belleau Wood was one of the bloodiest episodes in the history of the U.S. Marine Corps. At the cost of thousands of men’s lives, the Marines helped stop the German army’s last offensive. The battle established the Corps’ reputation as a fighting force. Today, Marines make pilgrimages to the cemetery and memorials there. In recent years, the USS Belleau Wood, a Tarawa-class amphibious assault ship, has been a staging platform for elite reconnaissance units making commando raids on hot spots around the world.

World War I was already an unimaginable horror in 1917, when the U.S. declared war. Records that my mother obtained from the National Archives show that my grandfather applied to the Marine Corps in Boston that Dec. 7 and was enlisted on Dec. 22, 1917 at the Marine barracks in Parris Island, S.C.

When he wasn’t tending animals and haying, my grandfather fished and hunted. Hunting proficiency made him a marksman at Quantico, Va. He embarked for France from Philadelphia on March 13, 1918, on the USS Henderson.

A military record contains notes about Roscoe Chase’s gunshot wound at Belleau Wood in World War I. (Photo courtesy Mary Ann Chase Vinton)

He arrived in France at Brest on March 26, according to papers we collected from the National Archives. Once in France, he became part of the 17th Company of the 5th Marines regiment that served with the U.S. Army 2nd Division.

The area around Belleau Wood doesn’t look all that different from Lincoln County. Fields of grain and grass are broken up by ravines and small forests. The Germans were entrenched with artillery and machine guns in the woods. The demoralized French were reluctant to fight.

The Marines charged the German positions and were slaughtered as they attacked, but kept going, eventually coming at the Germans with rifle butts, bayonets, and fists. Fighting lasted the better part of the month, with almost 10,000 Americans killed or wounded.

On our family’s tour, we walked through the fields and woods where my grandfather would most likely have fought. It’s terrible to think of the carnage he witnessed. Somewhere amid the fighting he was burned by gas that settled on him as he lay crouching for cover in mist and precipitation. It left permanent scars and discoloration across his back.

In later years he spoke little to his family about his service, although he shared some anecdotes about the large rats he saw in the trenches and a German prisoner in his care.

He recuperated in a hospital in Brest. He spoke fondly of the French, and told stories about a family with whom he stayed after leaving the hospital. He said he helped them with their farm work. They were elderly, and there was a shortage of able-bodied men.

Despite our best efforts, this last chapter remains a mystery to us. Who was this family? Where was their farm and under what circumstances did Pvt. Chase get paired with them?

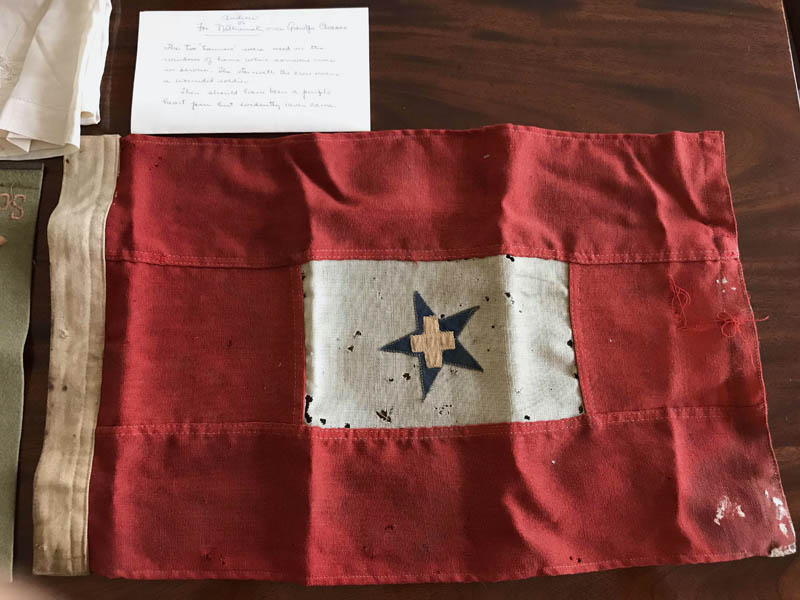

During World War I, families would hang banners like this one in a window of their home when a family member was in the service. The star with the cross means the service member was wounded. (Photo courtesy Mary Ann Chase Vinton)

Chase’s personnel records show he left France on Dec. 26, 1918, departing from Brest on the USS North Carolina. He disembarked at Hoboken, N.J., on Jan. 6, 1919. The record states he arrived at Marine Corps Base Quantico on Jan. 11, 1919. After furloughs, he was honorably discharged May 17, 1919.

We have a newspaper clipping from around that time – it lacks a date, byline, or headline – describing a memorial service in Sheepscot to honor the memory of Benjamin Reed, of Alna, who had been killed in the war. My grandfather was listed with the local men who served.

“The stars and stripes once more rose to the top and a salute was given in honor of Roscoe Chase, who though severely wounded in France is improving,” the piece says.

Roscoe died in August 1978 in Sheepscot and was buried in the Maine Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Augusta alongside his wife, Dorothy Carney Chase (1907-2002), herself a World War II veteran.

It’s not uncommon for veterans to take their wartime experiences into the grave. But if you have a vet in your family, my advice is to do all that you can to record a bit of their history – even if it’s just a list of dates, places, and unit numbers.

Somewhere out there in France is a farm where my grandfather helped with the harvest. If only we’d asked for the name of the town, we might have been able to track down the descendants of those farmers and ask them if they remembered a young American Marine, far from home but recovering from his wounds.

(Nathaniel Vinton is a former newspaper reporter living in Massachusetts. A graduate of Bowdoin College, he lived in Damariscotta as a child.)